Author and Workgroup Leader

María de los Ángeles Agrinsoni de Olivo

Co-Author:

Laura Santiago Díaz

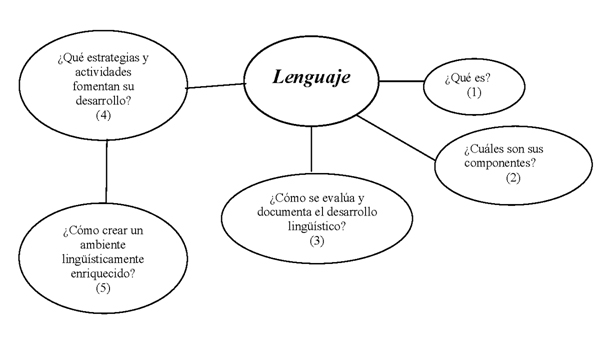

Self-Assessment

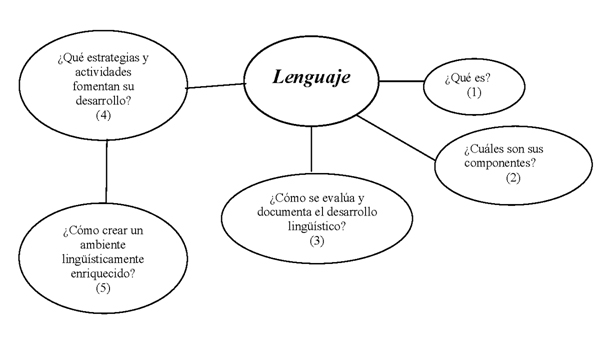

Complete this exercise in your Language Journal. Think about what you know about language as a concept. Complete the conceptual map, answering the questions that appear in the diagram.

Introduction

Introduction

Welcome to this learning adventure. The theme of this presentation is developmentally appropriate practices for language development. This module requires you to create a Language Journal in which you will complete the activities. You will need the following materials:

- notebook

- pen or pencil

- colored pencils

- felt-tip or magic markers

- crayons

- scissors

- glue

- construction paper

- ruler

The activities are organized in such a way that you reflect on your daily practices and consider new ways to use your learning environment. Remember to be creative. We hope that our work helps you to grow professionally. We wish you great success! Have fun!

This module is divided into eight sections that will aid you in creating linguistically enriched environments, where one learns the language and about the language, through the language. The eight sections are divided as follows:

- Language: A tool for communicating and understanding the world.

- Spoken language: Where it all begins.

- Our language system: Its uses and functions.

- Joy, pleasure, and passion… the reasons behind everything.

- A universe of ideas: The curriculum in action.

- Linguistically enriched environments… harmony and freedom.

- Enjoying and playing with language: Practical, relevant, and meaningful strategies and activities.

- Evaluating the process.

Language: A tool for communicating and understanding the world

¿Have you ever stopped and thought about how marvelous and necessary language is?

Language is the ability that humans have to communicate. It is the instrument that we use for social communication, based on a system of signs. The diversity of language includes both social and cultural factors. Communication is a form of human interaction that enables our collective understanding of the world that surrounds us.

Language is of utmost importance in the life of children. Human beings possess the capacity to process language, but this, by itself, is not sufficient (Chomsky, 1972). It is necessary that particular conditions are met in order to facilitate its development.

Upon entering a school or preschool center, teachers notice that all children are at different levels of language development. Why such diversity? Among other reasons, the youngsters come from diverse sociocultural backgrounds. For this reason we must remember that early experiences and the stimulation provided by parents, adults, and teachers in the children’s surroundings are decisive in the acquisition and development of language.

All early childhood educators have to face this challenge: to consider the particular needs of each learner in order to stimulate their language development and to do so in a manner that fosters their understanding of the world that surrounds them. Our goal is to develop basic linguistic skills in order to achieve more effective spoken and written communication. In other words, the teacher takes part in the process of educating individuals in the use of language as a tool for communication. What a great responsibility!

Adults play an essential role in the development of language use. We become collaborators in linguistic development. How do we do that? We use the following developmentally appropriate practices:

- Respect the child’s attempts at conventional speech.

- Remember that what we call “errors” (which, from now on, we will call “slip-ups”) are normal attempts at spoken language. For example: “She like cookies.”

- Encourage and enjoy their communication: listen and respond to the child correctly. For example: “You like cookies. She likes cookies.”

- Remember that these slip-ups are strategies that children use to conceptualize language and understand how it works.

- Get to know the proposed theories concerning language acquisition.

- Get to know the social and cognitive fundamentals of linguistic development.

- Be an alert and discreet observer who helps children instead of criticizing or judging them.

- Establish a relationship of mutual support with the children.

- Support linguistic development and be the child’s linguistic guide to the physical world.

- Translate the child’s physical, emotional, social, and cognitive world into words, in such a way that they are exposed to examples of how to express their needs, feelings, ideas, and experiences.

- Treat the assessment of their linguistic development with great importance.

If you are not versed in these areas, don´t worry. This module will provide you with the knowledge you need.

Activity #1

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal:

- Answer the following: What does language mean to you? What do you think about language as a tool for communication? What is its main function? How do you support a child’s linguistic development?

- Draw or diagram your answers to the previous questions. Remember to write down any additional thoughts or ideas.

Spoken Language: Where it all begins

Children are language learners by virtue of being born and living in society. They build linguistic knowledge through their use of language while interacting with other people and objects in their environment and while trying to understand the world that surrounds them (Halliday 1975).

The first manifestations of speech, such as gurgling, are a part of spoken language. This initial babbling is the infant’s response to adults as an attempt to communicate. It all begins when someone tries to communicate with the infant. Through spoken language, adults speak, sing, and explain the world that surrounds the infant; they translate the physical world into speech. At this stage, infants can “understand and hear the adult’s voice,” even though infants do not have the adult’s linguistic code system. As children grow, they continue to acquire more vocabulary and their thoughts, ideas, and expressions become more complex. Finally, spoken language reveals children’s knowledge of the functions of language, their level of interaction, and what they know about the world that surrounds them (Owoki & Goodman, 2002).

The best way to provide an enriched speech environment for children is by speaking, singing, and reading to them. These three activities complement one another and each one fulfills a special function in the development of language. When parents speak to their babies, they are preparing them for verbal exploration of the world that surrounds them. The sounds of the words are very important, as it will be the example that informs their speech.

From the very first moment, adults speak to newborns because we are sure that they understand us, and thus we are communicating (Asociación Mexicana para el Fomento del Libro Infantil y Juvenil A. C. 1995); in other words, we are certain that not only do they understand us, but that we understand them. It all starts when we begin speaking to them. According to Vigotsky (1978), spoken language plays a central role in the mental processes and the internalization of cultural processes. Spoken language reveals children’s knowledge of language’s functions, their competency for interaction, and what they know about the world that surrounds them (Owoki & Goodman, 2002).

The teacher’s role is to reinforce developmentally appropriate practices for language development. We carry out this responsibility by listening to what children say, and children should understand what we say. Through conversation and activities, children expand and refine their linguistic and conceptual intelligence. To the degree teachers listen and speak to children, they can, in turn, begin to understand the children’s thoughts and intentions.

Children learn as a result of social interaction and transform the language and actions of their social experience into tools for reasoning. Consider how the following example explains what was previously stated. María is five years old. She reads every day at her preschool. Every day, her mother picks her up and asks, “How was your day?” Looking at her mother, María answers seriously, “How do you think it went? It was a terrible, horrible, no-good, very bad day, just like Alexander’s.” María’s class has read the story “Alexander and the Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day,” written by Judith Viorst. María took one part of a children’s book she has been exposed to, changed it and made it her own, created an explanation, and responded to her mother’s question. The girl proved to be a successful language user. The social experience of her interaction with the teacher and with children’s literature has provided her with forms to express her feelings verbally. This shows how experiences with spoken language through the medium of children’s literature are a driving force in language learning.

Activity #2

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal.

- Answer the following questions: Has anything like this happened to you before? What happened? How do you interpret this experience now?

- Draw a few clouds. Each day, write in them the ideas that you talk about with your children.

Educators have to facilitate the use of spoken language. Developmentally appropriate practices consist of encouraging verbal interactions. It is necessary to speak to children in such a way that they can talk about their experiences and find practical solutions to the issues they confront in their daily lives. It is imperative that they participate in conversations that provide them with a respectful environment, characterized by the use of mature, not childish, language. A positive environment for verbal interaction encourages children to express themselves with confidence (Ruiz, 2003). Teachers must be willing to seriously engage children in conversation, listen to them, and respond to them with vested interest. Conversations can revolve around topics that interest them, such as things they like to do, how they do like to do them, and what they think about them.

Activity #3

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal.

- Answer the following question: What percentage of your daily routine is dedicated to speaking, singing, and reading to your children?

- Imagine that you are in the classroom’s play area. Draw a cartoon of what you are doing. Don´t forget to write out the dialogue.

We can state that for our practices to be developmentally appropriate, they must promote spoken language framed in the following manner:

- Speak, speak, and speak with the children, even if others claim that they do not yet understand you.

- Look for ways and situations for infants to speak and practice making syllables.

- Verbalize everything that you and the infant do. For example, “Let’s go play with the tennis ball. I like this ball because it feels soft.”

- Begin talking about different ideas and experiences. Even if the child is a baby, talk about what is happening and tell the child a story about your daily routine or a particular event.

- Encourage children to initiate conversation. You don’t want to control everything.

- Include children in your conversations, even if they do not respond conventionally. Use gestures and tell them that you love them. Look them in the eyes when you speak to them.

- Speak directly to them and articulate correctly and clearly.

- If they are already using conventional language, build upon what they are saying; complete, correct, and respond to the questions that they make.

- Explain to children that they can do things independently and solve their problems by talking about them.

- The goal should be an interaction between you and the children. Promote conversation and integrate speaking by playing with the children.

- Make up songs and oral stories for your children.

Activity #4

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal.

Review the ideas previously discussed. Think about which idea you should devote most of your attention. Prepare a contract and write down the practices that will play a larger, more important role in your daily routine, starting today. Remember to be creative!

Example:

- Invent oral stories for my children, at least three times a week.

- Bring a surprise box with something new to initiate conversation once a week. It could be something that I think is unknown to the children, a small animal, etc.

- Dust off children’s books from the bookshelf and make more time for reading out loud.

- Encourage children to speak more often.

I know that my enthusiasm and passion for my daily work will help me.

September 13, 2007

Date _____________________________________

Signature _____________________________________

Our Language System: Its functions and uses

Children learn to speak through the interactions they have with those who surround them in a language-rich environment (Weaver, 1994). As they learn, language becomes a tool for thinking. In other words, children will master language skills according to their level of involvement and their ability to solve situations faced in their daily lives. Children extract rules from the phonological, syntactical, lexical, and semantic systems by observing, listening to, and experimenting with language in its natural form.

The most meaningful way to learn a word is by hearing and using it in a spoken context. As they acquire language, children begin to understand it. Language development is related to the cognitive period when children begin to learn who they are (Piaget, 1959). Our role as educators is to encourage language as it is used to live, grow, and learn. According to the British linguist Michael Halliday (1993), before infants acquire a conventional linguistic system for communication, they already realize that language has meaning.

Through verbal exchanges, children learn the functions of language. Halliday’s research (1993) helps us to understand many of these functions:

- Language’s instrumental function – Language serves to satisfy a child’s needs. For example, a child may say, “Sip, Sip” and signal a sippy cup. The child means to say “I want”; in this case, the sippy cup as an instrument to satisfy their hunger, thirst, or something else unknown to us. Thus the child learns to use language as an instrument for obtaining the sippy cup. The adult may tell the child, “Do you want the sippy cup? The sippy cup has orange juice that tastes delicious. Here is the sippy cup.”

- Language’s regulatory function – Language is used to control others’ behavior. Children understand this early in their lives because language is used in this way with them. For example, an adult tries to control a child’s actions through negative expressions, such as: “Do it like I told you,” “Don’t touch,” and “I´ll do it, you do not know how.” Therefore, the child will try to do the same with the adult. Babies usually signal ‘no’ with their heads before signaling ‘yes.’ It’s logical for this happens. The adult has molded the child’s language. For this reason, we must use positive language with the child and avoid using ‘no’ in our interactions, unless it is for safety reasons.

- Language’s interactive function – Language is used to interact with the people around us. During early stages of development, children depend on adults to perform actions. The adult begins by demonstrating to them when to say “hello,” “goodbye,” or their name, and the children learn socially acceptable means of interaction.

- Language’s personal function – Language is used to express individuality and personality. Everyone is unique, and it is through our use of words that we come to know our true self. We express our likes, dislikes, interests, and feelings of pleasure. This stage is fascinating as children begin to demonstrate their interest by choosing the colors they like to wear or what they like to eat, among others.

- Language’s imaginative function – Children use language to create their own universe or environment. They invent a fantasy world. Children’s literature plays an extremely important role during this stage. The teacher should read to them from a variety of literary genres in order to enrich the child’s imagination.

- Language’s representational function – Children develop the notion that through language use they can communicate information and share knowledge, experiences, and observations about their world. With preschoolers, it is important to speak to them about topics they are interested in, to ask them what they want to learn, and to use informative books so they learn new information and construct knowledge.

- Language’s heuristic function – Children find the answers to their concerns, learn how things work, and discover that hypotheses are all constructed through language. Language is used to invent and question. Why are used to question and seek out the reason behind their mind’s troubles, whether they be unknown or novel.

How are these language functions assimilated? During the first few months of life, infants begin to articulate and play with their voices. When they are six to nine months old, their own personal sign system is expanded; it is converted into a language prototype. During this stage, the adult plays a predominant role. Based on regulative and instrumental functions, infants create their first system of meanings to satisfy their needs (Halliday, 1975).

At 24 months, children begin to create meanings, sentences, phrases, and expressions. Language helps them to construct dialogues, thereby discovering language’s interactive function. They expand their language; they develop more vocabulary, grammar, and structure. At 36 months, they discover the personal function of language and how this helps them express their feelings, interests, likes, and preferences. After this age, behaviors that indicate a search for information begin to appear and their experiences become more abstract.

Activity #5

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal.

- Answer the following question. Think about different everyday situations in which you interact with children. In what ways do you observe these functions in your teaching environment? Offer some examples.

- Draw a ladder with five rungs. On each rung, write what each language function means to you. One creative way to do this exercise is to draw an image or some representation of a child discovering what language is used for on each rung.

Little by little, children begin to understand and interpret what language is and the role it plays in their lives. According to Halliday (1975), children learn this three-fold approach of “learning language, learning through language, and learning about language” through practice and construction.

- Learning language – The fundamental factor in learning language is dialogue. This becomes an essential oral resource to understand the context and meaning behind what is said, to learn the form and sounds of language, and to recognize the role of the speaker. Children learn to express themselves in order to communicate. For this reason, we need to model clear and correct language and avoid “baby talk” and the overuse of diminutives. Also, we should avoid incorrect examples and isolated phrases, such as “John eat” or “Give hug.” It is better to speak in complete sentences, such as: “John, let’s eat this delicious rice, fruit, etc.” or “Come and give me a big hug.”

- Learning through language – Through language, we learn, build, and share knowledge. This process should not be reduced to a series of formal operations, like those of phonetics and isolated vocabulary learning. Actually, it is the mental process through which we learn how to learn and how to think. It is a tool used to showcase our ideas. It is the means through which we learn the content that we use in order to communicate. It is the responsibility of adults to provide appropriate feedback when what the child is trying to say is not clear. We must never belittle or admonish them for their limitations.

- Learning about language – At first, children learn semantics, grammar, and phonology without formal instruction. They construct their language, invent words, and play with language, transforming it into something personal. On many occasions, adults correct their underdeveloped expressions. However, children will repeat the same phrases again and again. Do not despair, it is a normal part of the constructive process. Little by little, they discover conventional usages, especially when they hold proper conversations. In this way, they acquire the norms of the language system by experimenting in natural, unforced ways. Educators do not dedicate their time to teaching specific grammatical structures, but rather create linguistically enriched environments in which children can listen and speak without fear of reproach.

Activity #6

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal:

- Are you creating an environment rich in language experiences that provides children a way of learning language, learning through language, and learning about language? How are you doing this? Make a list.

- Imagine that you are working on a campaign about how children begin to learn and interpret language. Design a poster that helps others understand that children learn language, learn through language, and learn about language.

Vygotsky’s theories help us to understand the evolution of language. In the first years of life, language is regulated by adults and the surrounding environment. These interactions result in children beginning to make use of words. However, the first words do not represent thought out acts, but responses to objects, people, feelings, or desires; as well as to what adults say to them. For example, the child sees something, signals it, grabs it, and the adult responds.

At two years of age, children can be observed demonstrating an active curiosity about using words. From this moment onward, children intentionally begin to learn what things are called. The classic question, “What’s this?” appears. It gives the impression that children experience a need for words. This behavior marks the moment in which speech begins to serve as a tool for intellectual thought. This is called verbal or conceptual thought.

Around three years of age, children begin to speak out loud for themselves: children become speakers. While they play and speak with others, they play out diverse roles within their daily environment. Vygotsky (1986) calls these acts egocentric speech. This event marks a shift in the child’s thinking, words are used to direct action; before this, action was initiated by the words of others.

Around five years of age, this type of language disappears and makes room for another type of thinking. Inner speech emerges. Children are able to speak to themselves without speaking out loud. Actions are more complete, and words begin to become imbued with sense and meaning.

Activity #7

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal:

- Answer the following questions: In what ways can language fortify thinking? How can you encourage children, by means of language, to reach higher levels of thinking?

- The International Reading Association has decided to organize a speech contest and you have been invited. They would like you to explain the following to the audience: How can we help children develop a solid command of language?These are the guidelines:

- Your presentation must not be greater than 250 words or less than 100.

- Your presentation should end with a two-verse poem.

Joy, Pleasure, and Passion… the reason behind everything

Now you know the importance of spoken language, as well as some principles of language development. Let’s apply this information to our daily practices working with children. Let’s recount some meaningful experiences with language use.

Enjoy this story about our infants and toddlers!

Apply it to your preschoolers!

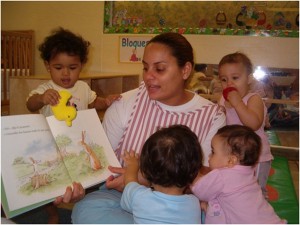

Yanitza, a preschool and nursery school teacher, sits on the floor. Her body, resting upon the mat, is like a rocking chair, her skirt, like the fluffiest cushion in the world. In the blink of an eye, Esteban sits on her lap and hands her a book. Two other children are behind her. Smiling and giving him a tender and affectionate look, Yanitza asks, “Do you want me to read to you?” Immediately, she begins reading the book. She opens it, and she slides her finger over each word as she reads it. She stops and makes a few comments, all the while keep visual contact with the children seated around her. In this setting, the children enjoy and relish their constant interaction with written and spoken language. The goal of this teacher is to promote holistic development through enriching experiences that show children how to optimize their physical, social, emotional, and cognitive potential. She was able to mold a balanced, independent, and happy human being who grows by exploring and discovering through the use of written and spoken language. She is certain that language is used as a tool for learning.

This teacher’s fundamental principle is the belief that language learning and learning to read and write begin much earlier than when children start their formal schooling. She understands that these processes start at birth. The teacher knows that she is a facilitator in the language learning process. Appropriate care requires oral communication through which infants and toddlers discover the world. Their cognitive development will depend, to a great degree, on an adult who sings, speaks, reads, and takes pleasure in rhymes and poems. All educators should be passionate and believe that children are not only capable of learning, but are knowledgeable beings.

Written and spoken language usage with infants and toddlers is part of their everyday environment. It is not something additional. Activities for linguistic development are commonly used when changing diapers, eating, and playing. Every moment is an opportunity to introduce ideas through the use of language. We should respond to babbling by having “conversations” with the infant, without baby talk, but in a nurturing tone, whose timbre stimulates the brain through the use of language that is appropriate and natural to the environment.

During the first year of life, mobility is of great importance. Adults encourage the child to sit up, scoot around, crawl, stand up, and walk. As educators, we do not separate these physical processes from linguistic or cognitive development. For example, we stand infants up, support them, and begin to gently bounce them up and down, all the while singing to them:

Grasshopper, Grasshopper

In the green grass.

Please do stop

And let me pass.

But it hops and hops and hops

and never stops.

Almost all the activities used for physical development can be accompanied by a linguistic activity. Our cultural tradition boasts many rhymes that accommodate interaction and movement, such as “Patty Cake,” “This Little Piggy,” “Itsy Bitsy,” “How Big Are You?”, “Touch Your Nose, Touch Your Chin,” etc.

Let’s not forget valuable resources like the rhyme books Goodnight Moon by Margaret Wise Brown and Llama Llama Misses Mama by Anna Dewdney. We highly respect and value the books of Dr. Seuss, such as Cat in the Hat, Green Eggs and Ham, One Fish Two Fish, and Horton Hears a Who. In these stories, we find a literature that is part of our literary and cultural heritage. In spite of the many years that have passed since their debut, they are extraordinary resources for linguistic development. These should be added to our list of everyday rhymes:

One Fish, Two Fish

One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish

Black Fish, blue fish, old fish, new fish

Some are red, and some are blue, some are old, and some are new

Some are sad and some are glad, And some are very, very bad.

All teachers should have a ready supply of rhymes, songs, and poems. They should alternate between them and continue to incorporate new ones, mostly from traditional literature. These can all be used on a daily basis in a circle or in a round. This is the moment in class when infants, toddlers, and preschoolers most enjoy songs and storytelling, whether they are laying in the teacher’s lap, seated, or standing. This moment must be organized as an outstanding event. For the infants, toddlers, and preschoolers, this is a conversation between teachers in which they incorporate the reactions and gestures of the infants and toddlers. Among the toddlers, dialogues like the following may arise:

Teacher 1: Mooo, Mooo Mooo

Teacher 2: Who’s paying us a visit today? Michael, who could it be?

Teacher 1: Mooo, mooo, mooo (who has a cow puppet hidden)

Michael: oo, oo, oo, oo

Teacher 2: I know who it is. It’s Linda, the cow!

During this exchange, the song “Old McDonald” is incorporated.

The children should not remain still. During this activity, they can move and dance to the rhythm of the bells, maracas, rainstick, xylophone, and drums. Everyone’s desire to move is respected. In the case of toddlers, it is clear that they respond to these songs, rhymes, and movements; even if they are in other areas.

It is exciting to see Rose, who is one and a half years old, take charge of the circle. She chooses what everyone will sing and acts out the movements for each song. Her classmates follow her. Consistently using circles as a strategy provides children with a means to develop language and to freely express themselves.

In the circle, we can use poster boards or printed sheets with songs that we prepare ourselves, and include drawings that illustrate the text. They are stored in one area of the classroom. Look at Mariluz, a year and two months old, pointing to the poster board that goes along with the song that is being sung (right after the song has begun). This shows the value in fostering real, relevant, and meaningful linguistic situations for children.

The environment is transformed when the fundamental objective is to promote language as a tool to discover the world that surrounds the children. As we continue to work and observe, it becomes important to change our way of teaching and acting. We can be inspired to try new ideas. One of our tasks is to create an environment for reading and writing. We do this so students can develop a relationship with printed material and a passion for reading and writing. We acknowledge our important role as teachers by constantly deciphering written symbols for our children. We become passionate linguistic guides who enable and promote their contact with printed material.

By filling our environment with books—lots of books—children enjoy picking them up, moving them about, examining them, or just playing with them (as is the case with the younger ones) throughout the entire day. Julio enjoys looking at and interacting with books, especially board books illustrated with photos of babies. He sits in the home corner, starts at the end and turns the pages until he ends up at the front of the book, and says, “baa, baa.” He seems to be describing the illustrations or what is happening in the story. It is significant that Julio does not use just one tone of voice. Each page prompts him to use a unique intonation. He also makes signs as he looks at each page. As long as we create enriching experiences that promote accessible language use, we will observe similar events every day.

To promote writing and language use through play-acting, children should be exposed to written material that they would find at home or in other familiar environments. Magazines, supermarket shoppers, and empty packages from beauty products should be kept in the classroom. For example, place a shopping cart and a register in one area of the classroom. Observe how the children react and guide them into the play-acting. Start by noticing the shoppers. Ask the children various questions, such as “Do you want to go shopping?” or “What do you want to buy?” Then, make a shopping list. Write down each item that they mention. While you write, pronounce each word out loud. At first, the children share by saying what they want to buy. They may not “write” anything down. Repeat this activity over the course of a few days, and soon you will notice that they decide to make their own shopping list and write on yours. In the following paragraphs, we offer other activities that strengthen writing skills.

Line the top of your arts table with drawing paper using adhesive tape. Using brown kraft paper, do the same to the wall and the floor. Gather thick and thin felt-tip markers and pens. Place the chalkboard on the floor, so long as it can be securely propped up. The teacher will be in charge of modeling the writing process. Children will go to this area and have fun writing and talking. Change the paper and poster boards on the wall every day. You will notice that the children will begin to hold the pen in their hands correctly, without constant correction.

Create a new area for reading, which we will call “the book pool.” Find an empty kiddie pool, place small cushions and books inside it. Convince the children that creating this reading area is a really “cool” idea, so that the children associate this with crawling through boxes, holes, and playhouses which are appropriate for their age. This will become one of their favorite reading areas. Encourage them to bring in their own books. The teachers too should have a space within the pool. Little by little, our enthusiasm will become contagious and the children will enjoy reading books.

Carolyn is part of a group that uses “a book pool.” At first, she would only lay on the edge and look at the books that the other children were exploring. A few days later, she too wanted to read, even though she only stayed for a short while before continuing on to play by herself. The next day, while she was alone in the book pool, she found a “peek-a-boo” book (in which you open little flaps or windows to discover new things) and she sat down with the book for ten minutes. How marvelous, a toddler who stays concentrated on a task for ten minutes! This is achieved by exposing children to the joy, pleasure, and passion of reading.

A favorite children’s story is The Hungry Caterpillar by Eric Carle. Using this book, you can make a felt puppet shaped like a caterpillar. Create the food that the caterpillar likes to eat. Allow the children to use and play with the puppet. You can hand out the different food items and narrate the story while the children feed the caterpillar.

These incidents are repeated over and over again in environments where passion for language is clearly evident. After reading The Hungry Caterpillar, place the puppets in the reading area. This will encourage the children to sit and play with it as a group. Without any one child taking the lead, the children will share the puppet and use their hands and arms to manipulate it, as if it were the caterpillar from the story. How wonderful! Joseph, two years and five months, begins to tell the story. He says, “the cadapila eat and eat,” alluding to the original story that says “the caterpillar ate and ate.”

One morning, the teacher comes into the carpeted area and sees Danny playing with the caterpillar.

Teacher 1: What´s this? (indicating the little bag made to resemble the chrysalis)

Danny: Crystalis

Teacher 1: What did you say, Danny? (surprised)

Danny: Crystalis

Teacher 1: Good job, chrysalis! And what does it turn into?

Danny: To a buddafi. (into a butterfly)

The teacher uses the reading chair for telling tales and creating stories. Leo and Genie sit on the teacher’s lap. They enjoy the book Noah’s Ark. The teacher gently rocks them, and Genie continues to suck her thumb and twirl her hair. From their vantage point, they follow the story’s illustrations very attentively.

Teacher 1: Noah and his family worked years and years to build a big ark. (turning the page)

Leo: (pointing towards a picture of a hippo) Da pi po.

Teacher 1: The hippo!

Genie: (Points as well and says) Da pi po.

Teacher 1: There’s also rats, crocodiles, penguins, tigers… (pointing to the illustration)

The toddlers look attentively at what the teacher is pointing to.

Genie: Da pen pen.

Teacher 1: (looking at Genie) The penguins. (continuing to read the story) Look at the animals, the elephants.

Genie: Pints.

Teacher 1: Elephants! (looks at Genie with a smile)

She continues reading:

Teacher 1: Look, what is this? Ahu hu hu hu! (making monkey noises) What’s this, Leo?

Leo: Monkey

Teacher 1: Remember that he lives in the jungle.

(Genie points to the monkey)

Noel: The monkey. (she says to Genie)

Teacher 1: It rained for forty days and forty nights.

Leo: (pointing to the moon in the illustration) Da moo, da moo.

Teacher 1: (continuing to read)…because it’s nighttime.

Genie: (pointing to another page) Me, me, me

Noel: A bird. (the teacher continues reading)

Genie: (starts pointing to the opposite page) Me, me, me

Teacher 1: These are birds.

Genie: Ba, ba, ba

Teacher 1: And Leo, what´s this?

Leo: Bird.

Teacher 1: It´s a hippo. And this, what´s this one? (pointing to the sun)

Leo: Sun.

The teacher uses this moment to sing “Here Comes the Sun.” Afterwards, they continue reading from the book and interacting.

(Teacher 1 turns the page)

Leo: (pointing out excitedly) Fish, fish, fish.

Teacher 1: Look at all the fish that live under the sea.

Genie: Fi, fi, fi, fi, fi

Teacher 1: Noah’s ark with all the animals inside. A panda bear, an elephant, an ostrich…

Genie: Fi, and Fishes

Teacher 1: Fish. This is the shark, the octopus, and the jellyfish.

Genie is a child who usually does not communicate easily with others. When she is sitting down and interacting during story time, her language skills become more evident. She tries to name what she sees. She repeats what is said. The use of books allows her to explore language. A competent student—in this case Leo—and the teacher—with passion—help her in a practical way. It is important to see Genie as having an active role, even if her pronunciation is not the most exact. She initiates and engages in conversations that she normally would not. What’s more, books help her to express herself, which she typically does not do with other children.

Orlando, Vanessa, and Alexis are in the reading area. Orlando has a plastic horse. Vanessa begins to flip through the pages of her book, showing the illustrations to her friends by pointing to them. Orlando comes closer and points to the pages as well. They begin to talk among themselves. Vanessa turns the last page of the book and finds only text and vocabulary without any illustrations. She looks at the page, and, all of a sudden, points at the words in the paragraph. She begins to speak as if she were reading the text. While she reads, she follows the text with her finger from left to right. She is properly holding the book in her hands. She demonstrates what she has learned thanks to teachers that have invested their time in demonstrating developmentally appropriate practices.

Vanessa grabs the book the same way her teacher does, with the back towards her and the front facing the children.

Vanessa: Da horse is ‘head. Ah Ah

She begins pointing to the text from left to right and says, “Ye, ye, ye,” imitating the sounds of a horse.

Vanessa, only two years and seven months, understands that we read from left to right and that we can read what is written, even if she gives the words her own meaning. Her favorite animal is the horse; therefore, she combines the text with the sounds that the horse produces. On the page is an image of the horse, and she creates a dialogue about something that she likes and is meaningful to her.

There are important elements that we can use to narrate stories. Discover the benefits of incorporating rhymes, poems, and songs into the narration of a story. We don’t just read the story, but add details that make the book more meaningful to the children. In the same way, we use illustrations to create a new story or to improve an established one.

In the story “The Little Princess,” there is an illustration of a spider. The teacher points out the spider on one of the pages. Eva, one year and eight months, begins to make the finger movements that go along with the song “The Itsy Bitsy Spider.” The teacher begins to sing the song. Then, they continue reading the story from where they left off. This happens frequently. For example, if the story is about pigs, we can sing “The Five Little Piggies.” If it is about tea, we can sing “I´m a Little Teapot.”

A teacher must make the decision to expose children to books with more text. There are many books in the reading area, including Baldomero va a la escuela [Baldomero Goes to School] by Alain Broutin and illustrated by Fréderic Stehr. The book has twenty-six pages, of which sixteen have at least four lines of text. It’s covered with contact paper to protect it from daily use (this should become a common practice to ensure a book’s longer life.) The teacher begins reading, and after a few pages closes the book and says, “Though it seems we just begun, our little story now is done. But don´t you fret, we´ll have more fun, and tomorrow we´ll start another one.” Without having finished, the children say, “No!” and open the book, showing the teacher the page in which the story stopped. At such a young age, children understand that books have a beginning and an end. During the telling of the story, they can predict and anticipate situations. The exact moment when Mrs. Frog tickles Baldomero the Bear, they tickle the teacher. Then, they scratch the teacher’s back, which is what happens later on in the story.

Oftentimes, children choose the person who will read to them. They have their preferences. This is what we call “reader attachment.” As teachers, we understand this process, as we know that it is a part of their socio-emotional development. When they choose their favorite story, the children all want the story to be read to them without interruptions. Peter approaches the teacher with a book. The teacher begins to read to him. He places his cheek next to the teacher’s and stays this way during the entire story, with his arm around the teacher. They share a tender moment, through the love of books!

These literary moments help balance temperaments and develop empathy. Carlos is a toddler who often bites others. His concentration is not as developed as other children his age. As we looked for alternative methods to help him, we didn’t realize that when he is read to, his concentration improved. Therefore, we would read to him whenever we noticed him getting anxious. His classmates would join him. As a result, the biting stopped and through reading he improved his concentration. He could not get enough of books.

Any given day, any classroom can be full of significant stories about reading and writing. These examples are not about children of above average intelligence or who are better than any other child. It is important to understand that they have been exposed to a great variety of oral and written experiences. Also, there are no limits on what they are capable of learning. Every day they are surrounded by teachers who believe that each child has great potential and that they learn with and through language. They feel joy, pleasure, and passion for language. Be inspired to use the strategies noted in these examples in your day to day interactions with your students.

Activity #8

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal:

Review the previously mentioned practices. Write a letter to another teacher explaining what a developmentally appropriate practice based on language development consists of. This teacher is anxious to learn practical ideas and apply them to her work.

The Universe of Ideas: The curriculum in action

In early education programs, the curriculum is much more than an educational plan that consistently organizes content and teaching strategies; it needs to be an integrated curriculum, or concerned with curriculum integration. This approach is linked to developmentally appropriate practices for children, as it takes into account the diversity (in terms of distinctive features), interests, and abilities of the majority of the children in the classroom or center. The integrated curriculum and developmentally appropriate practices have been considered two quality indicators in early childhood education programs for the last few decades (New, 1999). Both components reflect natural learning, development, and teaching.

What constitutes an appropriate curriculum for young children? For decades there has been a controversy on whether a curriculum for young children should be academic or more focused on the child, or if the curriculum and teaching should be determined by the teacher or be initiated by the child. Bredekamp (1987, 1997) outlined specific guidelines on developmentally appropriate practices for early childhood programs. These serve to guide teachers and establish that an appropriate curriculum should:

- Address and encourage every area of childhood development—physical, social, emotional, cognitive, linguistic, and cultural aspects—through an integrated perspective.

- Base the curriculum on the observations and documentation of the particular interests and the level of development of each learner that the teacher has made. The curriculum should be appropriate for the age, as well as the uniqueness of the individual. What is appropriate for one child may not be so for another child of the same age. Constant evaluation will uncover the strengths, needs, and interests of each learner.

- Conceptualize learning as an interactive process in which the teacher organizes, prepares, and offers an enriching and varied environment that facilitates active learning in children through exploration and interaction with adults, other children, materials, and other resources.

- Ensure that learning activities and materials are concrete, real, useful, functional, and relevant to the lives of the children. These materials should engage all five senses. Activities and materials should also be varied in terms of complexity and level of difficulty, in such a way that they are within each learner’s ability and potential.

- Provide sufficient breadth and flexibility so that the curriculum encompasses the full range of interests, talents, and abilities that may be manifest in the biological age of the group or exceed it.

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, the integrated curriculum has been identified time and again as a developmentally appropriate practice for young children (Bredekamp 1987). According to these guidelines, the curriculum should be integrated in such a way that learning of different subjects occurs through projects, learning centers, and interest centers. Essentially, Bredekamp is referring to the integration of materials, content, and activities.

A curriculum is integrated when different subjects are not presented in a fragmented or separate fashion. The Marco Conceptual del Programa de Kindergarten del Departamento de Educación de Puerto Rico [Conceptual Framework for Kindergarten Programs of the Education Department of Puerto Rico] establishes as a guideline that “kindergarten programs must work with experiences aimed at integrating different subjects and areas of development under a unifying topic” (Marco Conceptual del Programa de Kindergarten del Departamento de Educación de Puerto Rico, 2003).

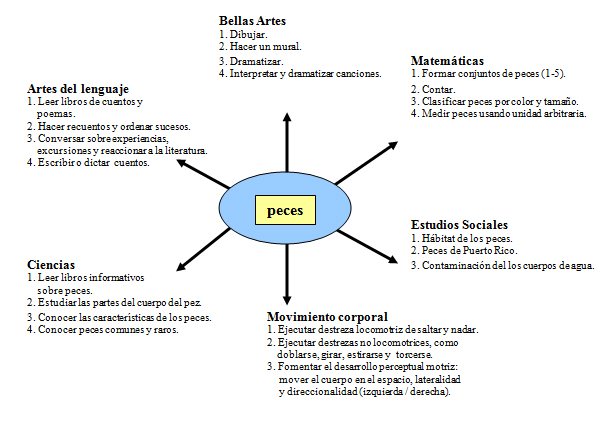

A great deal of literature and materials have been published to help teachers in the implementation of an integrated curriculum. In these publications, the integration of thematic units and cycles is developed as well as the integration of projects. Also, integration through the use of “webbing,” maps (of concepts and of curricular integration), and graphic representations of connections that exist between different themes and content areas is recommended (Lawler-Prince, Altieri & McCart Cramer, 1996). Let‘s look at an example of curriculum integration through “webbing” using the fish as a unifying theme.

The projects and thematic units are aimed at a deeper study and research of a topic of interest. Children develop concepts and skills through the integration of diverse curricular areas around the topic under investigation. In its 1991 publication titled Educationally Appropriate Kindergarten Practices (Spodek, 1991), the National Education Association published a few criteria to consider when selecting a topic:

- It should be appropriate to the age, development level, abilities, interests, and needs of the children.

- It should relate to the life and experiences of the children.

- It should consider the values and cultural diversity of each member of the school, community, and society.

- It should have the potential for deeper study through a variety of curricular materials and areas.

Source: Educationally Appropriate Kindergarten Practices (Spodek, 1991).

Activity #9

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal:

Do you know the guidelines for developmentally appropriate practices? Do you practice curriculum integration? How appropriate is your curriculum? Complete the following:

- Choose one of these topics:

- Animals of the Arctic

- Life in Italy (or any other country)

- Monuments of the World

- Climate Change

- Find information and children’s literature that will help you know more about the topic.

- Think of what would be interesting to know about the topic and make a diagram in which you can integrate different aspects of the topic into different areas of knowledge.

- Design a conceptual diagram.

- Think of activities related to the topic that would encourage language use.

- Create a diagram of other activities.

Children’s holistic development refers to their development in physical, social, emotional, creative, cognitive, and linguistic dimensions. We encourage you to avoid limiting the curricular content to one that emphasizes cognitive development above the other aspects of development. To do so would result in a restricted curriculum.

A vision that transcends and broadens the concept of an integrated curriculum places a greater emphasis on the role of the family, community, culture, values, beliefs, traditions, customs, social interaction, and childhood development habits (New, 1999). From this perspective, the concept of integration is much deeper and more comprehensive. New’s (1999) interpretation of an integrated curriculum incorporates the converging forces of the sociocultural context, the student, the learning environment, the teachers, the family, and the community as part of the curriculum. In this day and age, it has been demonstrated that these forces have an impact on children’s learning. In other words, integration in every sense is congruent with the learning principles presented by Vygotsky.

We cannot end this section without reflecting on the relationship that exists between an integrated curriculum, learning with meaning, and learning based on brain function theories. Taking into account the students’ previous experiences, interests, abilities, and the things they value is compatible with what is known about the brain’s learning processes. Providing an enriched, highly stimulating environment and establishing connections and relationships between new information and the children’s lives is also compatible with the brain’s learning processes (Caine & Caine, 1991).

Caine and Caine (1998) point out that the brain constantly seeks to establish connections and relationships and tries to make sense out of things and discover their meaning. In schools, however, the content of the subjects and disciplines is usually taught in a decontextualized manner that is unrelated to the student’s life or previous experiences. In order for learning to be effective, the teacher should establish relationships between the subject matter and the students’ lives and provide experiences that help strengthen neurological connections. Brain-based learning recognizes the relationships between different curricular contents (Caine & Caine, 1998).

Teachers design, facilitate, and organize these experiences and this enriched environment. To do so, teachers should be very creative and innovative. Likewise, teachers should present topics and content in an integrated manner (not fragmented or isolated) for children to have a sense of totality and unity. Caine & Caine (1998) suggest studying topics that are of interest to children, as well as using comparisons, associations, and multisensory representations.

Because language is the unifying element throughout an integrated and appropriate curriculum, the teacher should involve the students in significant activities that will require them to listen, talk, read, and write with genuine, real, and functional purposes.

Linguistically Enriched Environments… harmony and freedom

A linguistically enriched environment contains an abundance of experiences directly related to the lives of children and encourages the exploration of language (Ruiz, 1996). Some conditions that stimulate literacy and should be present in the linguistic environment are immersion, demonstration, approximation, and usage (Holdaway, 1979; Cambourne, 1988). A developmentally appropriate practice consists of immersing children in an environment where written and oral language are used in a meaningful and authentic manner every day by teachers who respect the attempts, approximations, and mistakes children make as incipient language users. These teachers understand that approximations are an essential part of the learning process.

One of the goals in environments where language is used as a communication tool is to provide multiple opportunities to involve children in reading and writing experiences that are real, contextual, and meaningful (Sáez, 1996). The literacy environment should have an abundance of meaningful printed material such as posters, books, signs, messages, tables, diagrams, magazines, large books, and material written or created by the children. However, simply being surrounded by printed material is not enough. Children should venture to use language. If the teacher does not, responsibly, provide freedom of choice and the opportunities for children to get involved with language use, the expected learning will not occur.

The literacy center is crucial in an environment that promotes integrated language development. For this reason, there should never be a lack of children’s literature. Children should be exposed to a variety of genres. Predictable books (books that contain rhyme, rhythm, and repetition) are especially important. Children love these books for their sonority. The repetition in the lines allows them to easily follow the storyline and memorize it. If you do not have this type of book, you can easily create this type of story.

Let’s do a test. Let’s write a predictable story. Our first line will be, “I’m happy because…”. Think of the things that make you happy. Every time you complete the sentence, begin a new one. Write your story in your language journal. What do you think of this one?

I’m happy because…

I live in Puerto Rico.

I’m happy because…

I’m surrounded by the sea.

I’m happy because…

I hear the waves.

I’m happy because…

I found a starfish.

Remember to create illustrations for your predictable story.

The reading area should be stocked with children’s literature by several choice authors. You should especially introduce children to Puerto Rican authors and illustrators. Here are some suggestions:

- Isabel Freire de Matos

- Ester Feliciano Mendoza

- Georgina Lázaro

- María Antonia Ordoñes

- Flavia Lugo de Marichal

- Marcus Pfister

- Eric Carle

- Keiko Kasza

- Frank B. Edwards

- John Bianchi

- Alma Flor Ada

- Tomie De Paola

- Ana María Machado

- Leo Lionni

- Anthony Browne

The reading center should include a variety of books. Try to remember if your center has the following books:

- Predictable books

- Cloth, plastic, and board books

- Wordless books

- Illustrated concept books

- Illustrated story books

- Classic literature

- Fables

- Poetry collections and songbooks

- Books with riddles or brainteasers

- Encyclopedias appropriate for the children’s cognitive level

- Informative books appropriate for the children’s cognitive level

- Interactive books (children can use their senses by seeing, touching, smelling, and manipulating them, for example, peek-a-boo books)

- Realistic literature that is appropriate for the children’s cognitive level

- Magazines and newspapers appropriate for the children’s cognitive level

- A series or collection of books based on a character (such as Clifford)

- Cook books

- Craft books

- Books written by the children themselves

- Books with commonly used vocabulary such as the names of the students, days of the week, months of the year, and names of the main characters in the books that have been read in the classroom.

The books should be accessible; they can be placed on racks or low shelves, in baskets, pinned to a clothesline, or in a shoebox with materials that are related to

the story. They should be identified and classified according to the topics that are being covered. The reading area should be comfortable and inviting, so that children will want to visit. It should include tables, chairs, cushions, a couch, a rug, and equipment to play pre-recorded stories. You can decorate the area with posters that encourage reading, and include a poster with the rules of the center. We recommend using a rotation system for the books and materials in order to keep the children interested.

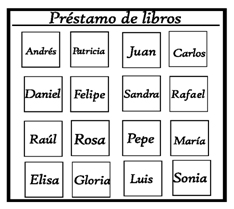

You can establish a borrowing system for books. Many children do not have the resources to have books in their homes. You can implement a control system that is easy to use and requires the least possible amount of help. We recommend making a poster for borrowed books that has envelopes with the name of each child. Each book should have an envelope inside the front cover, and in each envelope, a card with the title of the book. The students should remove the card from the book they are borrowing and place the card in the envelope that has their name and picture on it. When they return the book, they should remove the card from their envelope and place it once again inside the front cover so that another child can borrow it. Children who are old enough can do this on their own. Infants, toddlers, and preschoolers will depend on their parents, educators, and teacher for help. Note the following illustration.

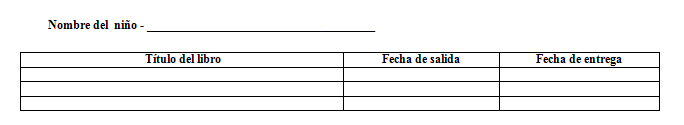

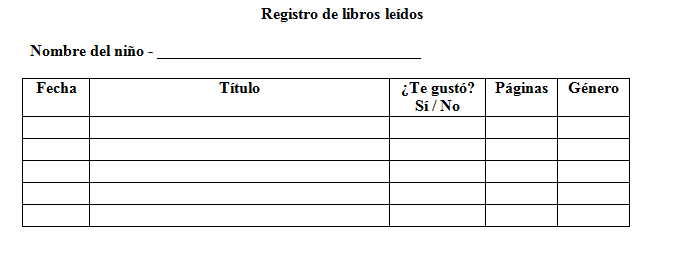

Another method entails keeping an individual record (in a table) of the titles of the books that have been borrowed and the date they were checked out and returned. Note the following example:

Children and their families must be informed about the book-borrowing project, the procedure involved, and the importance of taking care of the books.

The designated writing area should include tables, chairs, a chalkboard, and a computer. The writing instruments should include:

- A poster with an illustrated alphabet in English

- Wide-tipped and fine-tipped markers

- Wide and thin pencils

- Colored pencils

- Large and small crayons

- White and colored chalk

- Pens

- Stencils

- Various types of paper (white, colored, lined, plain, letter size, legal size, and large—24” x 36”)

- Construction paper

- Envelopes

- Magazines and newspapers

- Cut-outs

- Cards

- Post-It notes

- Strips of lined or plain poster board

- Stapler

- Scissors

- Book binding machine

- Books compiled by the teacher, in different forms and related to special occasions or different topics

- Decorative posters that stimulate reading

- A poster with the rules of the reading center

- A display for the children’s works and productions

- Plastic, wooden, sandpaper, and felt letters for play

- Chalkboard and magnetic letters

- Felt board

- Letter puzzles

- Individual mailboxes or cubbyholes

- Word bank

- Reading center sign

- Folder, portfolio, or binder for written material

- Play-Doh

- Dry erase board

- Brown kraft paper lining the wall

- Computer with word processor

Remember to make the necessary adaptations according to the children’s age.

Children should have a writing folder where they keep and collect their works and display their writing. It is important to record the date of each work to keep track of their process and progress. Basic writing materials, such as paper and pencils or pens, should always be present at every center and area of the classroom. For example:

- The home — Write messages next to the phone, write a shopping list.

- Blocks — Write messages, such as, “Please do not knock down.” “Built by Juan, Lisa, and Carlos.”

- Science — Record observations of the growth of a plant or fish on a table.

Remember, you are responsible for setting aside time in the daily schedule to visit the literacy center. A literacy center that is well organized, rich in materials, and accessible to children will encourage reading and writing (Ruiz, 1996).

If you have your own literacy center, congratulations! If you do not have one yet, go for it!

Tabs for Organizing Your Library

Catalog some of the books according to their level of difficulty and place them in containers or bins that have been previously identified so that children can choose according to their interests.

- Use different colored stickers to identify the topics of each book so that children can place them in the corresponding bins when they finish.

- Have large, predictable books available that have already been read in the group reading sessions, along with any related material.

- If possible, provide more than one copy of some of the books.

- Since picking up and shelving books can be tedious, you can use a compartment or basket for used books. At the end of the day, designate a helper to shelve them.

- Include a listening area for remedial readers. The children will love it.

- Catalog or group books by genre, topic, collection, or series.

Evaluate your center using this checklist

Reading Center Design

|

|

|

YES

|

NO

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The students helped design the reading center at some point. | ||

| 2. | It is located in a quiet part of the classroom. | ||

| 3. | The area is visible and physically accessible. | ||

| 4. | It provides comfortable spaces and separate corners for those who prefer reading alone. | ||

| 5. | It includes bookshelves or racks to store and organize the books in a way that is accessible to the children. | ||

| 6. | There is an organized system for storing and cataloging the books (color codes according to the complexity or topic of the book, strips with illustrations that specify the topic of each book). | ||

| 7. | There are special exhibition areas for new books. | ||

| 8. | There are at least 5 to 8 books per student. | ||

| 9. | There is a variety of genres and types of books: | ||

| • Illustrated concept books or picture books. | |||

| • Illustrated storybooks. | |||

| • Traditional literature. | |||

| • Realistic literature. | |||

| • Informative books. | |||

| • Books of poems. | |||

| • Fables. | |||

| • Legends and folklore. | |||

| • Biographies. | |||

| • Short novels. | |||

| • Easy-to-read books. | |||

| • Letters. | |||

| • Joke books. | |||

| • Riddle books. | |||

| • Craft books. | |||

| • Interactive or participation books. | |||

| • Book collections. | |||

| • Books series based on a person. | |||

| • Books from the same author. | |||

| • Cookbooks. | |||

| • Large predictable books. | |||

| • Magazines and newspapers. | |||

| 10. | There are books with a variety of topics. | ||

| 11. | There is a system for controlling and lending out books. | ||

| 12. | There are rugs, cushions, pillows, bean bags, etc. | ||

| 13. | There are tables, chairs, and couches. | ||

| 14. | There is equipment to play pre-recorded stories. | ||

| 15. | There are decorative posters about reading. | ||

| 16. | There are posters with stories, poems, and songs to read. | ||

| 17. | The area is marked and includes a poster with rules. | ||

| 18. | There is a felt board and stories with felt characters and scenes. | ||

| 19. | There is a catalog system for books that have been read. |

Activity #10

Complete the following exercise in your Language Journal:

- Observe your reading area.

- Take a photograph of the area or draw a sketch.

- Evaluate the area using the information you just read.

- Make a list of any changes you should make.

- Reorganize the area.

- Take another photograph or draw another sketch.

- Paste the photos or sketches in your journal.

Enjoying and Playing with Language: Practical, relevant, and meaningful strategies and activities

Young children should be exposed to the everyday joys and different uses of language. Storytelling and the presence of books from a wide variety of genres are essential. Every moment is a good moment to encourage reading. Every day we read for pleasure, to laugh, or to think. We need to erase the false notion that reading only takes place at certain moments or on certain days.

Teachers have many different types of strategies and activities at their disposal. Here are some examples of how to incorporate them into your daily routine. Try some out!

Reading Dialogues

Storytelling is necessary to bring books to life. The stories we read out loud become part of our lives; we make them our own. Through reading dialogues, we share ideas that relate to the story. The stories are transformed into different activities, such as text repetition, forming questions, and individual or group retellings of the story, to name a few. In reading dialogues, the child is an active speaker. By developing these reading dialogues, children make the texts their own. Soon, they will begin to ask questions about the texts and pay extra attention to the printed word (Molina Iturrondo, 1999).

Reading dialogues prompts children to have a conversation about the text. It is not just the teacher reciting a monologue. Therefore, the children’s “interruptions” should be encouraged. They foster dialogue. Do not anticipate the comments children will make, but listen to what they say and talk to them genuinely about their ideas.

Prepare for this activity with all the resources at your disposal. Take out your box full of puppets, marionettes, costumes, and anything else you have that helps you create a stimulating environment. Read with good intonation, articulation, pronunciation, and voice modulations. Apply the same techniques to storytelling as well.

Study and practice telling the story; this will afford you more confidence.

- Observe the illustrations slowly.

- Determine which details catch your attention the most.

- Interrupt the reading and initiate a conversation about any events or ideas related to the text that you thought of.

- Externalize the feelings that the reading produced in you and discuss them with the children.

- Ask questions, think about possible rhymes that relate to the text and integrate them into the story.

- Do not limit yourself to describing just the colors, forms, sizes, and textures that you observe on each page. Talk about other elements that help to construct meaning, to enrich the reading, and to expand the content.

- Play-acting: play out what you are reading or narrating. For example: blow out the candles if there is a birthday cake in an illustration. Eat the strawberries that are in the picnic basket, and when you taste them, act as though they are bitter.

- Include funny examples or other humorous elements.

- Use gestures, facial expressions, and different voices. Nonverbal language communicates, and complements, the text.

Remember that if they ask to be read to again, read to them with enthusiasm. This indicates that they enjoy and derive pleasure from reading. These reading moments are appropriate for children of all ages. There are even more types of reading that we can adapt to our environment, even with very young children.

Shared Reading

Shared reading is ideal for preschoolers. The idea is for children and teachers to read together. They should use large-print, predictable books. This activity consists of the teacher reading the text out loud so that all the students are involved in the reading process. The teacher uses this opportunity to model proper reading techniques. The reading should be repeated over the course of many days. This will inspire the children to read on their own later on.

Guided Reading

This is a strategy for small groups. You will need various copies of the book, so that each child has his or her own copy. The teacher helps them to realize that they can read by themselves. Teachers can point out the illustrations and characters to help the children predict what the story is about. After everyone has finished reading, they can share, discuss, or ask questions about the reading.

Independent Reading

The children choose what they want to read. Time can be set aside from the daily routine so that each child chooses a book and reads it. Then, they can share their impressions and can write about or draw what they just read. Those who cannot conventionally read yet can look at the books and make predictions. The children can read in the listening area.

It’s Storytelling Time

A good strategy to alert the children that we are going to read a story is to repeat a common phrase, chorus, or rhyme before beginning. The same one should always be used. Here is an example of a rhyming song you can use before story time:

Hello G’day

How are you today?

How are you today?

How are you today?Hello, G’day

How are you today?

And would you like a story?

If you’d like a story you just

Clap your hands (clap,clap,clap)

Stomp your feet (stomp, stomp, stomp)

Blink your eyes ( blink, blink, blink)

And nod your head. (nod)

That’s what I saidOR

Hello G’day

Shall we take a look?

Shall we take a look?

At a picture book?

Hello G’day

Shall we take a look

At a picture book today?

Enjoy Activities

There are many different activities that we can do with children to develop their language skills. These also serve to identify what kind of interaction the child has with the text. What does the text mean to the child? What are the child’s reading preferences? These strategies and activities help develop movement and written and artistic expression. Each one of these activities can be adapted and used with toddlers, preschoolers, or elementary school children.

1. Dioramas

These are three-dimensional representations of a specific scene from a story or topic. They can be made from a shoebox. Cut out the characters or objects that you want to place in the scene. Turn the box horizontally and glue the cutouts inside the box. For example, we could create a habitat or a scene from a text we just read.

2. Story Maps

You will need brown kraft paper, markers, and crayons. After reading, draw different places in the story that the characters visited. Encourage the children to draw roads, characters, legends, and different places. The idea is that these will come to represent a map. This activity helps children remember the events of the story. Remember that it is always perfect because it is made by the students.

3. Idea Quilts

After reading a text, the children can draw their impressions of the story on paper. Ask them what their drawings mean. Write down exactly what the children tell you and let them watch you write. Glue each work one next to the other, as if they were the patches on a quilt. You can glue three drawings per line. Later, display them in the classroom. You can do this activity for many different stories and add them to a previously made quilt. Eventually, you will have one large sheet.

4. Journals

You can do this activity by simply using a notebook. A journal can be made with different colored sheets of paper. After each reading, the children can write down or draw their reactions to the story in these notebooks.

5. Let’s Write a Letter

Children should select one character from their readings. Then, they should think of some questions this character might ask or things they might say to another character. They can write a letter together as a group. The teacher will act as the children’s secretary. The children can also write their letters individually. Remember to jot down all the funny things that they children say. With toddlers, we can write letters to mom and dad. We can spice up this activity by writing to the author of one of the stories we read. On the Internet, we can find websites of authors and illustrators that are willing to receive letters from children.

6. Semantic Maps or Webs

This is a way of graphically and visually represent the relationship between ideas and concepts; it serves to integrate literature, writing, oral discussion, and listening. There are many ways to develop a semantic map. After a reading session, everyone can decide on a topic, conflict, character, concept, or idea that they wish to research. This will be placed in the middle of a butcher sheet, within a circle or marked in some way. Draw lines from this center circle to different subtopics, comments, or ideas that come from the discussion of the text. For example, if the topic of discussion is dogs, a picture or illustration of a dog can be in the center of the sheet. Also, you could write out the word “DOG.” Semantic webs can be converted into concept or activity webs. The “dog web” can include its anatomy, breed, care, and food. If we make an activity web, we can include the activities that the children would like to carry out during their investigation of a dog’s life. This type of activity helps the teacher create lesson plans that address each child’s distinct interests.

7. Let’s Write Music

Using the events of a story, encourage the children to write a song. It’s easy to do. Ask them what happens in the story and write it out in a simple, short way. You can use portions of the text itself. In the case of predictable books, include the part of the text that is repeated. This can serve as a chorus. For example, this was a song written by preschoolers from the story “The Little Red Hen”.

The little red hen,

The little red hen

Went to plant the wheat

and asked help from her friends.

“Not me,” said the goose.

“Not me,” said the dog.

“Not me,” said the cat.

“I don’t want to help.”

And the little red hen,

and the little red hen

went to plant alone again.

8. Puppets and costumes

These can be created by using materials typically found in classrooms. Use puppets during your storytelling sessions or songs. You can make them with paper plates or bags, toilet paper rolls, disposable spoons, fabric, cereal boxes, felt, and brown kraft paper. Since this activity is designed to encourage creativity, let the children choose their favorite puppet characters so that they can create new stories with them. You can also make costumes for the children using only brown kraft paper. Fold it in half and make a hole in it large enough for the child’s head. On the paper, children can draw pictures that allude to the character. You can also turn a piece of fabric into a veil or cape. Now you’re ready to pretend! Keep a notebook to record the children’s spontaneous play-acting.

9. Posters

With repetitive sounds

For this activity, you need to use predictable stories that have sounds or words that are repeated throughout the book. Books that contain lots of onomatopoeia and alliteration are excellent for this activity. The idea is to keep brown kraft paper or poster board in the classroom, and as you read, identify which sounds are repeated in the story and write them down on the paper. This is not a one-day activity—do this every day. Once you have finished making the poster, identify a rhythm and turn it into a song. Another game you can play with your students is to read the poster at different speeds.

Below is an example comprised of sounds found in the story “Giggle, Giggle, Quack,” by Doreen Cronin and Betsy Lewin, and in the book We’re Going on a Bear Hunt by Michael Rosen and Helen Oxenbury.

Giggle, giggle, quack

Giggle, giggle, oink

Giggle, giggle, moo, giggle, oink, giggle, quack

Giggle, giggle, moo

Giggle, giggle, quack, giggle, moo, giggle, oink

Swishy, swooshy

Swishy, swooshy

Splash, splosh

Splash, splosh

Squish, squelch

Squish, squelch

Remember that you should make this poster with the children so that can better relate to it. Don’t make the poster by yourself. Children will always choose new sounds to include in the poster. You can develop choreography or a series of movements that go along with the sounds.

Advertising posters

Write the upcoming classroom events on the poster. You may advertise special events, the book of the week, or the title of the story you are writing.

Wanted posters