Author and Work Group Leader:

Annette López de Méndez

Co-Authors:

Nereida Rodríguez Rivera

Carmen E. González Nazario

Isabel Vázquez

Self-Assessment

Imagine that a mother who would like to enroll her three-year-old son in preschool comes to your classroom. She has many questions about what that experience would be like. Read every question and in your own words, write out how you would answer the parent’s questions:

- What kind of experiences would my child have in preschool?

- How will the school day be?

- Will he have time to play?

- What will he learn? Will he learn to read and write?

- What kind of teaching methods will be used to motivate him to learn?

- How will his progress be evaluated? How will I be informed about his/her progress?

Once you finish the exercise, save the document with your answers to these questions. When you finish studying the module, you will need to answer the same questions and compare your answers with your previous ones.

Introduction

The purpose of this module is to help educators clarify the concept of “curriculum” and understand how appropriate practices can help us make decisions on the expectations, routines, materials, and methods of both organizing the surroundings and performing evaluations. It also contains theoretical content, which has been divided into related topics, and it ends with an application and reflection exercise. I invite you to begin reading this module by reviewing the objectives and the self-assessment. When you finish the module, you will find references and links that will enable you to continue exploring the concepts that have been covered.

Objectives

- Define the concept of “curriculum” in my own words so that I can use it to establish appropriate methods and learning experiences. This will also help me to select educational material and evaluation strategies that are on the learning level of young children.

- Understand the meaning of Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) so that I can organize and design an appropriate curriculum.

- Understand the importance of play and the way it contributes to the development of physical, social, intellectual, linguistic, and creative aspects, with the purpose of planning and modeling experiences that are based on play.

- Establish structured, attractive learning environments in areas that invite children to explore their surroundings and interact with other children and adults.

- Construct an integrated curriculum for young children that offers enriching experiences that will promote their investigative abilities, creativity, problem solving, humanism, and language.

The Appropriate Crriculum

Curriculum: A Definition

A curriculum is a written plan that establishes goals and objectives and suggests the learning activities and experiences, the educational materials, and the strategies to be used to perform an evaluation. In the case of young children (0 to 6 years old), this plan is used to establish a list of guidelines so that the educators can make appropriate decisions concerning the educational process. This curriculum embodies the philosophical vision that defines the educational program.

For children between 0 and 3 years of age, the guidelines function as a model for the educator to establish appropriate expectations for early child development, methods of organizing the surroundings and daily routines, types of games and activities that include children, materials and strategies aimed toward stimulating different areas of development in infants, and methods of working with parents.

For children between 3 and 6 years of age, the curriculum suggests goals, methods of organizing the surroundings, and a series of daily routines. It also contains information and teaching strategies that are directed to promote physical, emotional (intelligence), linguistic, cognitive, and aesthetic development. Likewise, it establishes guidelines to understand, promote, and evaluate the child’s development, and suggests ways to establish positive interaction with the parents and the community.

A curriculum is…

Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) and Curricular Development

The Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) designed by the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) are defined quality standards that help educators select and plan effective and adequate educational experiences that are independent from existing curricular foci. They promote the following values in educators:

- Meet the children’s needs at their level of development (physical, social, emotional, and cognitive).

- Identify adequate goals and make sure that they are not only attainable, but also challenging to all the children.

- Understand that educational methods will vary person-to-person depending on individual levels of development, experience, knowledge, abilities, and the context where the learning experiences are being offered (Copple & Bredekamp, 2006).

Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) for early childhood enable educators to make decisions—which are related to the teaching-learning process—that vary by and adapt to the individual ages, experiences, interests, and habits of the children, within a given parameter of age (from birth to 3 years old and from 3 to 6 years old). Also, these practices ensure that young children learn:

- When they interact with adults who love and respect them and who are able to respond to them in a positive way;

- When they interact dynamically with the objects and the world surrounding them—playing, exploring, experimenting, interacting with other people, handling and touching objects—these experiences contribute to learning in a specific way and make use of all the senses (seeing, smelling, hearing, tasting, and touching);

- About significant experiences—children learn better when they can make connections between what they know and what they are about to learn;

- When they are allowed to build their own knowledge—it is important for adults to give children time to figure out experiences on their own;

- By playing—play is fundamental to learning, since it allows children to solve problems, make decisions, talk, and negotiate.

The Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) for child development define the following five aspects as guidelines that should regulate our educational practices:

- Create a caring community of learners, in which everyone feels like they belong and are in a safe environment where they are just as important as everyone else. It is a place in which we learn together, and if there are problems, a solution can be reached through dialogue. By working together and collaborating, great things can be achieved.

- Teach to enhance development and learning. Good educators use a wide variety of teaching strategies, in which they: give children positive attention when their behavior is appropriate; motivate them in a positive way to persevere and do their best; model appropriate behavior; offer specific feedback; offer structure and challenges, as well as information and direction; know how to organize learning in a step-by-step way; vary the work for large and small groups; promote play; allow them to work on the areas of learning; and during the day, structure a routine of activities, but keep them flexible.

- Plan an appropriate curriculum. Educators establish clear and precise goals for learning and know how to plan them adequately to assist in the emotional (intelligence), linguistic, mathematical, and technological development in children. These goals also contribute to their knowledge and scientific inquiry, their understanding of themselves and their community, their creative expression and appreciation of the arts, and their abilities and physical development.

- Assess children’s development and learning. Educators know alternate ways to evaluate and monitor children’s learning and development. They use the results of the evaluation to guide and plan their teaching and make decisions; they analyze the results to detect and identify the children who could benefit from special support and services; they inform and communicate the strengths and needs of the children to others (parents, specialists, health professionals, and others) so that these people can participate in an effective way in the teaching-learning process.

- Develop reciprocal relationships with the families. Educators establish relationships that are characterized by mutual respect, cooperation, shared responsibilities, and negotiation of differences with the children, the parents, and the community, in order to achieve a common goal.

Explain in your own words how the following five aspects that guide the Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) can help us design a better curriculum for young children.

- Creating a caring community of learners means…

- Teaching to enhance development and learning implies…

- Planning an appropriate curriculum means…

- Assessing children’s development and learning implies performing activities directed to…

- Developing reciprocal relationships with families means…

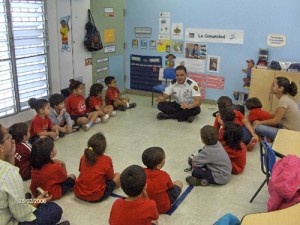

Curricular foci that exemplify Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP)

Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) are not a curriculum; they are guides and principles that can assist educators in making decisions about the curriculum. Montessori, High/Scope, and Reggio Emilia are curricular foci used in both public and private preschool centers in Puerto Rico as well as in the United States that illustrate the use of Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP).

Montessori Focus

The Montessori focus is considered both a method and an educational philosophy. It is based on the observation of the characteristics of children in different stages. The following educational environments should be structured for each of these stages: birth to 3 years (Infant care), 3 to 6 years (La Casa de Bambini/Preschool), 6 to 9 years (Primary 1), and 9 to 12 years (Primary 2). The activities are structured and differ according to the level of development.

The educator’s role in this focus is to serve as a guide, and thus observe and structure the environment based on the children’s needs and interests. The environment is divided into different areas of learning and the educational materials are placed on easily accessible shelves so the children can freely explore and select what they wish. The activities are ordered from simple to complex, and their purpose is to promote sensory, physical, intellectual, and spiritual development. The work areas for the preschool environment are identified as: sensory, practical life (gracefulness and courtesy), academic and cultural topics (language, mathematics, social studies, and science), artistic expression, and music.

The Montessori environment is characterized by its emphasis on: (1) freedom of movement and selection; (2) external structure that promotes internal order; (3) beauty, reality, and naturalness; (4) an atmosphere that promotes respect for life and a sense of independence; (5) the use of materials that promote learning; (6) and community and family life (Lilliard, 1996; Montessori, 1965; Standing, 1962). Parents are considered a fundamental element in children’s development and they play a vital role in increasing their children’s learning.

To know more about the Montessori Method, you can go to: http://www.montessori.edu

High/Scope

This model is based on the theories of Jean Piaget, who states that children learn when they interact with the people and objects around them. This constructivist viewpoint (DeVries & Kohlberg, 1987; Kamii & DeVries, 1978, 1980) focuses on cognitive ability learning through experiences that allow children to touch and to do. The adult creates an environment where children learn dynamically and build their own knowledge base.

The educator’s role consists of observing, planning, and organizing the environment, as well as stimulating positive relationships with the students, and encouraging dynamic learning. In this type of environment, the educator promotes learning by using the scientific method and stimulating children to ask, experiment, deduce, and make predictions.

On the preschool level, the educator encourages students to plan the tasks they want to accomplish during their plan-do-review sequence, according to the different learning areas. These areas are divided into the house area, block area, language area, mathematics area, science area, art area, water area, sand area, among others. An activity that characterizes this focus is working in small groups, which is directed to helping children plan their learning experiences with the help of the educators. The work periods are long (45 minutes or longer) so that the children can plan, play, and complete their tasks. As part of the daily routine, the educators also structure the periods for:

Thinking in a systematic way about the tasks the child wishes to perform;

Separating time so that the children can accomplish the plans that were talked about and established with the adult;

Picking up, cleaning, and organizing the classroom—offering children the time to return the materials to their place, which will contribute to the feeling of order and beauty;

Reflecting on and discussing achievements;

Working small groups in order to actively explore the materials and interact with adults and other children as well;

Spending time in a large group so that the students can sing, exchange ideas, and hear storytelling, thus developing their social abilities.

The key experiences in High/Scope are structured around the following topics: movement, music, numbers, space, time, and creative representation, as well as language and literacy, initiative and social relationships, and classification and series. One of the responsibilities of educators is to keep a careful record of the child’s development. Both the educators and the parents are considered experts who are capable of contributing to the children’s development.

To know more about High/Scope, you can go to: http://www.highscope.org

Reggio Emilia

This focus emphasizes cooperation, collaboration, and organization between educators, parents, and children (Gandini, 1993). Their educational goal is to provide positive relationships and learn to collaborate and appreciate the diversity of ideas in their various expressions. The curriculum is organized into topics selected by the children, and later transposed into a learning project. The excursions into the community, working with recyclable materials, and searching for solutions to everyday problems all promote the development of their abilities and competence. In the Reggio Emilia focus, art is considered one of the many forms in which children are able to express their learning. Each school has an atelierista, or art teacher, who participates in developing projects so that the students can express their learning in a creative and artistic way (Edwards, Gandini, & Forman, 1998).

The environment is designed to promote communication, exploration, learning, beauty, and aesthetic sense. Parents are considered central to the curriculum and participate actively in the classroom by cooperating with educators and children. One of the educators’ responsibilities is to document in detail the children’s development, using photographs, artistic representations, and transcriptions of the conversations and discussions with the students.

To know more about Reggio Emilia, you can go to: http://zerosei.comune.re.it/inter/index.htm

|

Curricular Model

|

How do they exemplify the Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP)?

|

|---|---|

| Montessori | |

| High Scope | |

| Reggio Emilia |

Principles to Consider When Designing a Curriculum

An appropriate curriculum will serve as a tool to help educators make decisions about the design of the educational goals, the objectives, the learning, the learning experiences, the teaching strategies, and the methods of evaluation. Every educator who follows the Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) should consider the following principles when organizing and designing the curriculum (Bredekamp & Copple, 2004):

- In an integrated manner, nurture and encourage all the areas of human development: physical, emotional, social, linguistic, aesthetic, and cognitive;

- Include a variety of content by way of the different subjects, in order for the content to be socially relevant, challenging to the intellect, appropriate, and significant for children;

- Design learning activities based on children’s knowledge and abilities in order to consolidate what they know and stimulate their acquisition of knowledge;

- Use integrated planning to promote sensible learning that is both deep and wide, in order to cultivate rich intellectual development in children;

- Encourage the development of knowledge and comprehension, of processes and skills, as well as the ability to use and apply these skills for children to continue to learn;

- Teach the curricular content in a way that reflects the concepts and tools of inquiry determined by the various subjects, using strategies that are accessible and appropriate to the children’s level of development;

- Provide opportunities to support the children’s culture and vernacular, and encourage them to develop their abilities to be active in the culture of their program and community;

- Establish realistic and attainable curricular goals for each age group or level;

- Whenever possible, knowledgeably integrate technology into the curriculum, using equipment and programs that are appropriate for the children’s level of development.

The curriculum must also provide or adapt educational experiences to inclusively attend to children with special needs. To accomplish this, the planning and implementation of the curriculum should include a variety of strategies for assessment and evaluation that emphasize observation and documentation of each child.

What principles of the Developmentally Appropriate Practices (DAP) can you identify in Mary’s decisions?

¿Qué principios de las prácticas apropiadas puedes identificar en las decisiones que ha tomado María?

The game as a fundamental element in the development of curriculum

How Do You Define Play?

Instead of being a frivolous, pointless activity, play is considered by educators to be an activity that promotes learning in children and stimulates their development. Its value lies in that it is something natural for children and it impels them to explore and learn about their environment and interact with people and objects. Through play, children handle and interact with objects, which provide opportunities to develop their physical, intellectual, and emotional (intelligence) competence.

What Benefits Does Play Have for Early Childhood Development?

Intellectual development can be encouraged through games, since they involve multisensory experiences through which children can touch, handle, observe, etc. If we observe children building things with blocks, making a road, playing with cars, using puppets to retell or invent stories, or counting tokens to see who has more, we can see how these games stimulate development in all of its dimensions. For example, blocks offer the chance to learn geometric shapes, learn vocabulary, solve problems, and comprehend abstract symbols. At the same time, they help refine children’s physical (pincer grasp—necessary for writing), social (cooperative work), and emotional (sense of accomplishment) development. In this type of play, cognitive development is immediately associated with language, which underlines the importance of encouraging dialogue while children interact with objects.

Play is an activity that focuses on the process (Bruner, 1972). It offers children the opportunity to experiment to see how things are done without fear of failing or making mistakes. When a child plays, there is no correct way to do things. Instead, it is an action guided by the question, “How does this work?” This way, when the children throw a ball, their interest is focused on watching it bounce and roll to understand its characteristics.

Social development is stimulated when children play “mommy and daddy,” pretend they are the teacher, or imitate roles. When children engage in play-acting, we can observe how they learn and define social roles, and as a result, their social interaction skills are being developed. We can also encourage their social development through other games, such as playing ball with another child or playing circle games. When children have to negotiate roles—determining who is the mommy and who is the daddy, playing with others, or participating in group games—this helps diminish egocentrism. Group games help them begin to clarify and comprehend the limits and rules of social interaction.

Vygotsky (1978) tells us that play allows the preschoolers to understand the consequences of their actions. For example, a child who plays “mommy and daddy” should learn to obey the limits and rules associated with those roles in order to maintain the sequence. He also states that play provides children with challenges that develop their intellect when they can apply what they know or they encounter new experiences that require more complex behaviors.

Play stimulates the development of written and oral language. The willingness and interest in learning a language can be observed when infants babble and make sounds. When toddlers play with the language system (imitating sounds from the environment and making up words), they speak through a puppet or telephone, draw freely, or try to copy letters from the alphabet. Experimentation and creation of language is apparent when they play with sounds, whether on their own or with their friends, and when they play with the structures of words and how they form sentences. Using rhymes motivates them to learn the meaning of words and sharpens their ability to identify sounds. Drawing and scribbling that imitates actual text show us their interest in writing. This highlights the importance and necessity of creating environments that are rich in language development, where children are not simply heard, but are surrounded with books and tools to paint, draw, and write. Adults nurture language development when they talk, respond, sing, and read to children. A language-rich environment also promotes art in all of its forms so that children can familiarize themselves with multiple forms of expression and communication.

The hands are a child’s learning tool. We stimulate their physical development when we encourage them to touch and move freely. Their gross motor skills are motivated by activities that involve the entire body, which is why it is important to encourage children to walk and move around. Fine motor skills mainly employ the muscles in their hands and prepare the child to use a pencil and to write. It is important to estimulate these abilities and help children be aware of their bodies and space in order to develop their sense of direction. Likewise, it is important to provide many opportunities to practice all their movements by crawling, sitting, grabbing, shaking a rattle, throwing and pulling objects, putting puzzles together, building Legos®, dancing, going down a water slide, running, moving objects from one place to another, stringing beads, playing with water and sand, riding a bicycle, planting, cutting out and pasting, among others. Body movement, dance, and music are essential elements in an environment designed to stimulate holistic development.

Managing social conflicts and feeling good about oneself are important elements in emotional development. In order for children to participate in games in which they interact with an adult or with other children they must acquire coordination and cooperation skills. This social play can be divided into several types: social play with objects or with adults, parallel social play (plays alongside other people and imitates their actions, but does not interact), associative social play (similar to the previous type, but participants share verbal messages), and cooperative social play (two or more children coordinate their actions, exchange information, and assign roles for each other). Play-acting is on a higher level than social play because play-acting involves the following: imitating roles; imagining objects, actions, and events; establishing interaction with others; communicating verbally; and being persistent. This highlights the importance of teaching children to follow rules during the game, just as they should in peek-a-boo and in circle games. The following are some examples of ways the educator can encourage emotional development in children: teaching them to dress themselves, tie their shoes, comb their hair, and solve everyday problems that arise during games, as well as being an example of gracefulness and courtesy when asking to borrow an object, for permission to speak, to move a table, among others.

Elkind (1981) points out that play provides children with opportunities to understand and work with difficult situations. For example, after a child is told she is going to have a baby brother, we would likely see her pretending to wash and dress the new baby. In this case, play allows her to adapt to a new situation that for some children could cause an emotional burden or even great anxiety.

Creativity is intimately linked to play, since children easily imagine things using objects. Educators can motivate their creativity by observing and encouraging children to discuss their ideas, and by praising their creations. Their creativity could involve building a house with boxes, painting imaginary animals, dressing with cloth and papers, seeing different things in objects or making different things out of them, and inventing words and songs. Creativity is also linked to developing positive self-esteem. Praising and displaying their work is a way of reaffirming each child’s value.

Reality is suspended during each game. Children use their imagination to immerse themselves in creative, spontaneous activities that cause them great joy and satisfaction. Through these re-enactments, such as playing school, children can practice social roles, develop their vocabulary, and explore the role of a teacher. When children select their own games, they develop their sense of independence and diligence. It is as if they are saying, “I can.”

|

Game

|

Area of development that is cultivated

|

Role the educator can assume

|

|---|---|---|

| Shake a rattle. | ||

| Throw a ball with various colors and textures. | ||

| Turn the pages of a book. | ||

| Place boxes inside of other boxes. | ||

| Draw and color with crayons. | ||

| Talk with an imaginary friend using a telephone. | ||

| Play circle games. |

Share your list with others to see how their ideas compare to yours. You can also invent your own games to determine the type of challenge they will present for each child.

The Role of Adults in Play: Plan, Model, and Observe

Educators should observe and interact with children. For this, it is essential to first plan the environment, and second, plan the times designated for each task. Planning the learning experiences will depend on the educator’s ability to observe and talk with the children in order to better comprehend their interests, strengths, and needs. Before starting the day, the educator should determine what objects to place in the environment and should have a clear idea of the use and didactic purpose of each object. Then the educator should invite the children to play by using a deliberate, pleasant, and enthusiastic voice. The educator should model the way to handle and use the objects, and then give them time to examine, explore, and use it on their own. The educator can then take advantage of that time to observe them.

While the children work, the educator observes and calmly encourages those who need help. When infants play, the guide assumes the responsibility of providing objects for them, talking to them, and encouraging them to play. As the children grow, the activity can become parallel. The educator sits and plays alongside the child and quietly talks through what is taking place. When the children are ready to interact with others, the educator can ask them what they are playing and how to play, provide feedback, and participate either from within or from without. If the child invites the educator to play, the educator will take advantage of the opportunity to model appropriate conduct or to serve as a tutor in the game. But, if the educator is observing from outside the game, he or she can provide feedback or guide them with questions.

Games are genderless, so it is important to ensure that all the children be invited to play in the different areas or learning centers. Educators must provide activities that appeal to the interests and learning level of children in order to motivate them to participate. Play also provides a good opportunity to integrate cultural diversity by exposing them to games and songs from other countries.

How Do You Work with Children who Have Problems Playing?

Some children have difficulty playing with others. This can occur for many reasons, which include shyness, lack of experience, feeling out of place because of unfamiliarity with the game, emotional trauma (like the loss of a family member, divorce, moving, among others), abuse, negligence, speech difficulty, or intellectual disability. In any of these cases, it is very important to seek help from specialists, learn about the specific situation, and refer the child to receive any help that may be needed. However, we must provide them with the same opportunities and attention as the rest. It is our responsibility to help them feel good about themselves and invite them to participate without obligating them.

Early Childhood Curriculum: Creating a Suitable Learning Environment

The design of the curriculum must emphasize that learning is an interactive process. Teachers prepare the environment so that children can learn by exploring and dynamically interacting with adults, peers, and suitable materials. Understanding children’s average development within the range of possibilities for each age provides a broad point of reference for whoever designs the curriculum. This allows them to design an environment with suitable goals, objectives, and experiences. The fact that there are huge differences and variations among children of the same age is simply another factor in determining the development of mental maturity. Likewise, studies in neuroscience reveal that the brain cells in children from infancy to 10 years not only form the majority of the connections that will remain the rest of their lives, but also this stage provides the greatest possibility of modifying their development (NAEYC, 2004).

The decisions that are made about the curriculum and the interaction between adults and children should be as individual as possible. This implies that even though we should establish goals and expectations for all children, these goals and expectations should be flexible to accommodate individual differences, which are a result of the biological aspects of development and the learning experiences in their early childhood. Consequently, it is important to know the children’s sociocultural and familial context to better understand their development.

In this stage of their lives, most infants and toddlers are in infant care locations. If we take into consideration what we mentioned before, we will understand why it is important, when planning a curriculum, for educators to organize the learning experiences in a way that will contribute to the child’s optimum development. This implies structuring integrative experiences into all the following areas of development: physical, social, emotional, and cognitive. Quality care in the beginning stages of growth can make a difference in the lives of children, and can even predict their academic success and adjustment to school. It also serves to minimize problems in their behavior in first grade (Howes, 1998 en NAEYC, 2004). In the following paragraphs, we suggest ideas that should be considered when structuring the environment and activities for infants and toddlers.

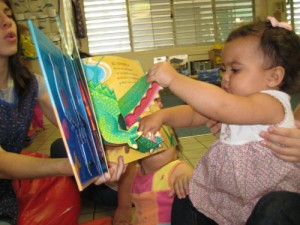

Infants (birth—9 months) – Every baby is unique. Newborns differ in the way they learn, use their senses, and respond to stimuli. However, all babies need a safe environment where they feel cared for and loved by their primary caregivers. From birth, babies are actively engaged in building their own knowledge through their experiences, which are measured by and tied to their sociocultural context. Babies enter the world prepared to establish relationships, and they express this with sounds, facial expressions, and movements. These are also used to communicate their needs and feelings. Babies enjoy language and they learn by moving their hands, feet, and the rest of their body. For infants, frequent contact with other people and the opportunity to touch and feel objects as they explore their world is of utmost importance.

Since every baby is unique, the caretaker’s task is to observe and learn to recognize the infant’s individual needs, eating and sleeping routine, reaction to new things (including other people), and preference for the way he/she is held when being fed or put to sleep. A child’s sense of security and confidence is developed as long as the caregiver acts predictably and provides interesting experiences.

Planning the infants’ day revolves around structured routines for the following activities: changing diapers or clothes, feeding times, and sleeping periods. The environment for these activities should be prepared very carefully. It must be clean to protect their health. It should have an area for hygienic articles (diapers, soap, cleaning wipes, and others.) next to a sink. It should also have an area for feeding, with comfortable couches for mothers who come to nurse and high chairs to feed babies who have begun to eat solid foods. Likewise, a designated sleeping area, where each infant has his/her own cradle, should be used exclusively for sleeping.

When the routines are pleasant, infants learn that their needs and bodies are important. An environment that is adequately organized should provide an open space where children can crawl and move about freely (while they are constantly observed by an adult). In this area they will have varied opportunities to find objects that capture their attention, which they can examine, touch, and handle, arousing their curiosity and need to explore the world at their own pace. Educators will establish a time in the routine to take the children out to walk around in the garden. They will also include periods to listen to music and sing lullabies in order to encourage the children’s language development. The educator should always speak to the children in a gentle, deliberate voice so the children can easily associate the actions with the words.

Another important aspect that the educator must consider is the transition phase between the home and the care center. When infants are placed in a center after having established a relationship with their parents or primary caregivers, they must build new relationships. It will take time to adjust to the differences they will sense in touch, new tones of voice, and the sounds and objects that make up the new environment. To minimize the impact that these changes will have on the infant, it is important to establish some sort of bond between the caregiver and the parents, based on constant, daily communication. Both parties should set aside a time to gather important information about the child’s health, habits, achievements, and eating patterns, to name a few.

If you were Ms. Carmen, what would you do to foster communication with José?

Infants (8 – 18 months) This stage is characterized by greater mobility and the development of their sense of identity. The infant will actively explore the environment and seek adventures, but will need to feel safe and supported. The educator’s role consists of offering unconditional support to the infants, encouraging them with visual contact, talking to them, and making gestures of acceptance. If infants feel they are supported, they will develop a feeling of trust and self-assuredness that will enable them to accomplish more. In this stage, the environment should be spacious, safe, and attractive. The routines will be different from when they were younger, since the infant will spend more time awake and will need new experiences. The experiences can be exciting, challenging, pleasant, or frustrating. Playtime should include time to crawl, climb, walk, and examine objects.

At this age, infants imitate and mimic facial expressions to express anger or sadness. This is the first step in play-acting, through which children practice what they see and experience in their environment. In this stage they can distinguish between the familiar and unfamiliar. They show anxiety with people that are not familiar to them, although the level of their anxiety may differ. They will occasionally latch on to objects—pillows, an article of clothing from either parent, a particular toy—that will aid them in becoming more independent. While in the care center, educators must use simple sentences, encourage them to use sounds to communicate, and provide time to listen and show interest in figuring out what the infant is trying to communicate. Educators must also provide time to listen to music, sing, and experience rhythm by playing clapping games, thus boosting communication and their sense of independence.

It is important to create a safe environment where children can move around comfortably. Educators must provide loving, watchful care. They should calmly establish boundaries and give them clear and simple explanations.

What things can María to do encourage Nina and Tere to explore?

Toddlers (16—36 months) During this stage, the child’s search for identity, interest in exploring, and need for security and independence are foremost. Children are observed establishing relationships with their peers, in which case, support from adults is necessary. Children also show a fascination with words and language at this stage, and begin to use words to communicate and interact with others. Their routines are different from those of previous stage, because play becomes the primary activity.

The educator’s role consists of observing the children, fostering their development, and making sure to maintain a balance between the need for activity and inactivity, or in other words, play and sleep. The routines must be organized to provide a balance between active and passive activities. The environment must be spacious, safe, clean, and attractive. It should be organized into different areas, with different materials placed at the children’s level so that they can choose the activities on their own. The educator should also encourage them to: play outside, walk, jump, sing, look at books, draw, do puzzles, and play with other toys.

During this stage, conflicts will arise because children will have difficulty understanding other people’s points of view. Despite the fact that it will be difficult for them to share their toys with others, the educator can structure activities to encourage cooperation. When children do not get what they want, they often react impulsively and show their frustration. However, with the help of an adult they can learn to wait and negotiate. This will help them grow as social beings, learn to follow rules, cooperate, and be considerate to others. Educators have the duty to provide children with opportunities to develop their sense of responsibility (by caring for plants and animals), learn to face challenges (by trying to do things over again), make decisions, and receive discipline (by establishing limits and understanding the consequences) without losing their dignity. To accomplish this, the environment must have clearly defined limits, and the educator should be consistent with the rules of conduct. In this way, children will be able to develop their personal and social confidence.

What could Ms. Isabel do to get Pedro to join Joel and Karina?

Preschoolers (3—5 years old) During this stage, children go through qualitative as well as quantitative changes in their development. The environment must be geared toward encouraging independence, language, symbolic thought, relationships between others, cooperation, and motor control. This will require a spacious, attractive, safe area that will promote holistic child development.

Physically, children seem to endlessly walk, run, hop, jump, and play actively. Since the environment provides space to promote coordination in their movements, it must be spacious and must have access to a yard with play equipment.

Linguistically, children continue to expand their vocabulary and transition from simple sentences to more complex ones. They move from having difficulty carrying on a conversation to being able to listen to others, and from interrupting to being able to contribute their ideas. Because the adult is their model, it is important to speak to them correctly in a soft, measured voice. In this age span, children have a great opportunity to learn a second language with ease. Reading stories, playing with puppets, play-acting, singing, and chatting with children are some of the activities that should be included in the curriculum in order to cultivate language. Language should be present throughout the environment. A language area that contains storybooks and materials to draw and write should be included.

Cognitively, developing symbolic thought is important. To accomplish this, the environment should promote the re-enactment of daily situations, memorization, prediction, as well as the use of language, logical reasoning, the imagination, and creativity. The house area and the block area are important for children’s cognitive development. Other aspects that should be taken into account when designing the curriculum include being egocentric, focusing on one characteristic at a time, learning through concrete experiences, attributing human characteristics to inanimate objects, and having short attention spans. The curriculum should take these aspects into account and promote cooperative work using specific examples to teach different concepts. It should encourage children to talk about their experiences and should include long periods (an hour or longer) for children to play, organize projects, and explore different concepts.

Peer relationships are essential for learning social, emotional and moral conduct. Playing with peers allows them to discover the limits and consequences of their behavior. Since different fears appear in this stage, it is of utmost importance to promote trust in their relationships with adults. It is the educator’s responsibility to ensure that the children realize that each one of them is important and has worth. The educator will also guide them in understanding right from wrong by offering opportunities to learn from their mistakes.

What can Ms. Cristina do to foster Eduardo’s independence and his sense of accomplishment?

Learning Centers and Their Role in the Curriculum

Learning centers are specific areas where we can place materials and equipment that facilitate holistic development in children. These areas allow us to integrate the knowledge, abilities, and values established in the curriculum. Depending on which curricular focus is used, we will see several different learning centers, such as language, library, home, blocks, manipulatives, mathematics, science, water and sand, and art and music. In each area, children will find shelves with educational materials that have been placed within their reach, organized by subjects, and arranged from simple to complex. Educators will present the materials to the children so they can use them as often as they need. That way, the children will be able to explore different concepts individually or in small groups.

What other materials would you suggest that Mr. Pedro place in the other learning centers?

- Language: ____________________________

- Library: ___________________________

- Home: ______________________________

- Mathematics: _________________________

The Role of Learning Centers and Educators

The primary functions of learning centers are to organize knowledge, develop language, and provide the materials needed to explore concepts through a specific experience. Educators are responsible for periodically changing, cleaning, and organizing the materials in the areas in order to convey a sense of order, integration, and beauty. The areas must invite and motivate children to explore and ask questions. The educator must arrange the environment in such a way that children will “learn by doing” and will interact with objects, other children, and adults.

The educational materials and the selected activities should be specific, real, and relevant to the lives of children. An attractive environment will stimulate them to choose freely, handle the materials, and reflect on their work. Educators model, guide, and observe children as they work. The mistakes children make are seen as learning opportunities and are used to help and promote their learning.

Educators promote individual, small group, and large group work. They also encourage children to learn from their schoolmates—this encourages cooperation and the development of social skills. The routine is flexible, but the work periods are established and defined, such as welcome and greeting (everyone in a circle to begin the day), small groups work (4 to 5 children) in the different areas (45 minute periods or longer), recess or outside play (individually or in groups), story time (everyone in a circle), and individual work (to practice different skills and abilities).

If you were Ms. Astrid, what would you do? Would you continue to observe or would you help him put the puzzle together? Explain your answer:

The Area Designated for Language Development

Reading and writing are a fundamental part of any curriculum, as they decide the success that children will have at school and in the future (Neuman, Copple & Bredekamp, 2001). Language acquisition is a continuous, evolutionary process that can be observed from birth. Generally speaking, the first years of infancy (0 to 8 years old) are crucial for language adquisition. For babies, crying is a way of communicating with adults. As they grow and recognize the voice of their caregivers, they respond by cooing and making other sounds, eventually saying their first words: “mama,” and “papa.” In head-start/preschool, infants quickly begin to master words, fragments, and short–or telegraphic – sentences. At the preschool level, the children’s vocabulary expands because they like to ask questions, hold conversations, draw, and imitate writing. Language learning begins in an informal way and it is therefore important that the environment be carefully planned in order to promote language arts (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) in young children.

Learning reading and writing is a complex, multifaceted process that requires a wide variety of techniques (Neuman, Copple & Bredekamp, 2001). For this reason there is no particular teaching method (Strickland, 1994). On the contrary, good teachers use an endless number of strategies to reach children. Reading out loud is one of the most important strategies to develop interest and love for reading and writing (Wells, 1995; Bus, van Ijzendoom, & Pelligrini, 1995).

How can we plan a language-rich environment?

- Prepare a language area that includes different types of books with photographs, illustrations, and objects to pair, stories, paper of different shapes and sizes, crayons, colored pencils, small chalk-boards and chalk, felt boards, magnet boards, foam letters, a place to hang up the children’s creations, a computer with reading and writing programs, tables and chairs for writing and drawing, a reading chair, cushions, a rug so they can lie down and look at books, shelves that are accessible to the children on which there are picture, poetry, story, non-fiction, and other books.

- Integrate reading and writing materials into all areas. For example, put a sign on the door with the name of the classroom and the teacher, put up a calendar with the name of the month and days, make and display labels with the children’s names so that they can be used to take attendance, label objects that are in each of the areas, place books in the areas related to their topics, among others.

- Include reading and writing activities in the daily routine. For example, read the children’s names to verify attendance every day, distribute menus for the daily meals, use a calendar and schedule sheet to promote reading, read and re-read a story every day during class time, sing songs and illustrate the lyrics with flash cards.

- Speak with the children, tell them the names of objects, show interest in their questions and comments, encourage them to talk about their experiences, describe their ideas, and verbalize their thoughts.

- Show them books, read and re-read their favorite stories, refer to letters by name and the sound they make, encourage them to explore and associate the relationship between sounds and letters, play word games such as riddles, rhymes, songs, and group games.

- Show them how to use books: how to flip the pages, how to follow the text from left to write, what is the book cover, where is the author’s name. Read texts and stories that are age-appropriate and which include rhythmic language and simple vocabulary (illustrations accompanied by words or short sentences, illustrated short-stories, non-fiction books with predictable stories). The themes should touch upon daily life and the values and interests of the children.

- Encourage the children to draw and experiment with writing. They should be encouraged to choose topics that interest them, emphasizing that they are writing for a real audience (their peers, parents, and friends). First the educator should encourage them to converse and then to draw. The role of the educator will be to translate and transcribe the drawing into a regular text. When the children already recognize letters, the educator will invite and motivate them to write the letters of the alphabet and a few common words that will go along with their drawings.

- Allow time each day for the formal teaching of reading and writing. Every day the children should be read to in order to create experiences in large and small groups so that they can explore words (letters and sounds), draw, and write. Also, there should be individualized activities so that the children’s development can be documented and analyzed.

- Allow sufficient time for the children to speak, read, and write. Observe and encourage their development while documenting it through portfolio projects that track the evolution of their learning and help to understand their learning problems, all while respecting the differences in learning levels.

- Take field trips to libraries, museums, and community sites so that they can speak and write about their experiences.

- Encourage parents to participate in the reading and writing process, ensuring that they know the program well and are familiar with the experiences created by the educators in their centers and emphasizing the importance of having books at home. Emphasize also the importance of reading children their favorite stories every day, offering them opportunities to draw and write at home, go to the library, museums, and zoos, concerts, encourage them to sing, to write notes and letters to their grandparents, relatives, and friends, help them to learn how to use computers and navigate the Internet. You can also create a system of book-lending in the classroom so that children can take a book home to read with their parents every day.

- Foster respect for cultural diversity by integrating stories and folkloric tales, as well as traditional family practices of the children, into the curriculum.

The Designated Area for Encouraging Contact with Nature and Science

A large part of the joy and enthusiasm that children experience when they are outside the classroom stems from their contact with nature. Observing nature – the smells, colors, and textures – offers them the chance to be in contact with real objects in real situations. Touching the ground, smelling a flower, seeing a lizard up close, and seeing other animals in their natural habitat allows children to make associations between various aspects of life and teaches them to approach nature with respect, encouraging a sense of protection and care toward the environment and the planet.

To plan a game and experiences of the outdoors the educator can offer children the chance to plant different types of plants that grow with a minimum of effort, taking into account their developmental stages. Parents and community members who are interested in contributing to these initiatives can participate in planting these seeds and enjoying nature’s processes. Also, a representative of an organization that works to defend the environment could be invited to share knowledge about endangered plant and animal species.

What Can We Do?

- Make contact with nature an integral part of the daily routine.

- Include walks and excursions in the vicinity of the school or center, taking into account the children’s ages (infants, toddlers, preschoolers).

- Have materials in the classroom that are related to nature and that stimulate creative play.

- Plan camping trips (even if they are just activities in the classroom) and encourage the children to seek out the materials they would need to carry these out, get colleagues and parents involved. Be sure to follow health and safety regulations (considering allergies, for example).

- Collaborate with colleagues and parents, and plan visits to places where children can observe and have contact with animals while learning about them.

- Encourage children to make up stories related to their experiences with nature (about the rain, the sea, storms, trees).

- What color is this hibiscus?

- How many petals does it have? Let’s count them.

- Why don’t the petals fall off?

The girls observe the flower and explain to the teacher that the petals seem to be sitting inside a green cup. Rosa tells them: “Yes, that part of the flower is called the calyx. Would you like to put the flowers in a vase with some water to keep them alive and decorate with them?”

Analyze this situation and explain why Rosa is exploring nature with her students.

The Arts as a Complement to Learning and Development: Music, Visual Arts, and Drama

The arts stimulate creativity in children and are a complement to their emotional expression. It is important to offer them the freedom and materials they need to explore, in their own special way, the joy of artistic and musical experiences. It is amazing what an educator can notice when observing the children’s artistic creations and how art can be integrated into each discipline. Art is a universal medium of communication that allows humans to relate to each other, independently of the various meanings found in art.

The Association for Childhood Education International (ACEI) recommends that all children have the opportunity to express themselves through art. In their guidelines they state that the international community needs inventive, ethical individuals with the resources, and capacity to make significant contributions to problem-solving, not only in our current Information Age, but also in the years to come.

Diego, a five-year-old boy, is very animatedly playing with some cars. He has a favorite car that he has not been able to find and says something to the teacher. The teacher tells Diego to make a drawing of his steps when he was last playing with the car. Diego makes the drawing and finishes at the spot where he left the car – and there it was!

The arts have always been seen as a central element of any curriculum. Henniger (2005) citing Bruce, notes that the arts motivate children and involve them in the learning process, stimulates their memory, fosters symbolic communication, promotes interaction, and provides an avenue for skill development. The arts are a natural process for children. As they grow up, both physically and mentally, they continue developing the designs made as infants and toddlers into a more defined work in their first years of primary school.

The art component of the curriculum should be well defined regarding the opportunities and experiences it offers to the children. Educators should be very careful in the selection of materials and supplies that they provide in the art activities in the classroom. Some examples of things that can generally be found in a preschool center are the following: paper (in different colors), crayons, chalk, colored pencils, markers, scissors, tempera paint, and brushes. These items should be useful in whatever the children do. The important thing is to be very careful so that the materials do not get broken and are put back in an orderly fashion. This will keep the children from getting upset and allow them to enjoy their experience.

How can educators provide artistic experiences in their classrooms?

- Provide children the chance to explore using the materials and equipment in the classroom.

- Increase the difficulty, complexity, and challenge of the activities according to the children’s skill-development stage.

- Rotate the materials in the different areas of the classroom so that the children develop an interest in different things.

- Show interest in the children’s creativity.

- Give positive feedback on the children’s work so that their self-esteem is boosted. For example: “Alana, what a great blend of colors! Your picture is going to look great!” This is a healthy way to draw attention to the importance of each of the children’s work.

- Describe and demonstrate the appropriate use of tools and materials.

- Take advantage of these activities to allow children to create freely without having to give them models to follow and showing them the “correct” way to make art. This will help them develop their creativity.

- Display the children’s work in the classroom or in some other place and make sure they are easily visible to the children.

- Take the children to visit museums, exposing them to different techniques (painting, drawing, sketching, photography, sculpture among others) and the works of different artists, especially those representing Puerto Rican culture.

Music

Just as with art, the foundation for interest in music and development of musical skills is laid in early childhood. Studies show (Ball, 1995 in Henniger, 2005) that the potential for learning to make music develops at the age of nine. Many educators and parents are aware of this reality and allow children to hear a variety of musical styles, and to sing, dance, and learn to play an instrument from a very early age.

Music is a subject that has received a great deal of attention from educators in general, but especially from those working with young children. There are many songs written especially for various stages of development and there are many reasons to include these in the curriculum. Isenberg and Jalongo (2001), as cited in Henniger (2005), among others, have pointed out the benefits of music in children’s development:

- Language

- Self-expression

- Improved memory

- Concentration

- Social interaction

- Fine motor skill development

- Listening

- Problem solving

- Team work

- Creativity

- Family relations

- Self-esteem and confidence

- Emotional development

- Oral expression

- Cultural understanding

- Perceptual skills

- Affective development

Music stimulates the neural connections in the brain that are associated with the higher forms of intelligence such as abstract thinking, empathy, mathematics, and science.

The melody and rhythmic patterns of music provide exercise for the brain and help to develop memory. For example, the letters of the alphabet can be learned by children when they sing them.

Music helps children develop good listening habits, which are essential for academic success. Researchers have studied the development of musical abilities in children and, like Henniger (2005), they describe their results in terms of typical ability depending on age rather than defining results based on developmental stage:

- Infants – react to the softness and tones of voice of other people.

- Toddlers – distinguish sounds, hear music, repeat some phrases, enjoy creating music.

- Three-year-olds – they control their voice and sing simple songs, they can play instruments (drums, maracas among others).

- Four-year-olds – they can sing complete songs from memory, classify musical instruments according to sound, shape, and size, learn basic musical concepts, develop their singing voice.

- Five-year-olds – they sharpen their sense of tonality, rhythm, and melody.

- Six to eight years old – their voices mature a little more, they develop a sense of harmony and musical preferences, they are able to show an interest in musical instruments.

- Children’s movements

- Facial expressions and body language

- How they interact with the other children

- Their creativity

Write about your observations in the space provided:

______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________

Mathematics

Teaching and learning math can be a fascinating experience depending on the activities, strategies, and materials that are used. The idea that a child is an active participant in learning, applied to math, can lead to engaging many topics in which children can explore and discover real connections to the world that surrounds them.

During early childhood, children develop the comprehension of essential mathematic concepts that will help them in future learning. This guides to the mastery of particular skills, such as:

- Ability to classify – this entails the ability to group objects and ideas of similar characteristics. Educators can use different objects to reinforce this capability: stones, lids, blocks, pencils and others.

- Ability to place objects in order – organize toys, for example, from largest to smallest, by weight, or size.

- Ability to create and recognize patterns, whether they be spatial, visual, auditory, or numeric.

- Ability to understand numeric concepts. During the first years, children learn to count forward and backward, by twos, and know the numbers up to 100.

- Ability to quantify and measure objects. For example, figuring out the height, weight, volume, and dimensions of an object.

- Geometry – Studying shapes in two or three dimensions and how these are related. Although it can seem like a topic for older children, the world is full of different shapes that small children like to explore.

Using Technology

Nowadays, technology, whether simple or complex, has become an essential part of our daily lives. This fact is also true for our children. From a young age children are surfing the Internet with amazing ease, in large part due to their exposure to computer games. Researchers have also documented the associated potential benefits for learning and development.

Educators recognize the importance of offering opportunities to access computers from a very early age, using them as an effective tool for exploration, learning, and play. However, they have the responsibility to critically examine the impact of technology on children and how to use it to benefit them. The position that NAEYC takes accounts for different topics related to the use of technology by young children:

- The role of the educator in evaluating the technology.

- The potential benefits of the appropriate use of technology in early education programs.

- The integration of technology into the everyday environment and in daily learning.

- Equal access to technology, including for children with special needs.

- Stereotypes and violence in computer games.

- The role of educators and parents as mediators.

- The implications of technology in professional development.

In their guidelines, NAEYC uses the word “technology” primarily in relation to computers, but it can be extended to cover telecommunications and other multimedia devices.

Research indicates that, in practice, computers complement rather than replace activities and materials that are highly valued in teaching children, such as art supplies, building blocks, sandboxes, water, story books, and items for play-acting.

How has this experience helped to make technology a learning tool? If you have had a similar experience, how did your students react?

Educators have to make judgments constantly about what is appropriate when choosing what programs to use for their students, considering, for example, age, individual compatibility, cultural and social diversity, social background, and ease of access.

Did You Know That…?

- The right program for the children’s developmental stage can offer them the chance for creative play, learning, and creation.

- Educators should evaluate the cost of technology in relation to the use of other materials.

- Technology provides children with the opportunity to evaluate their own learning and to repeat processes so that they can master skills they have problems with.

- Children prefer to work with people their own age rather than working alone with computers.

- Technology has benefits that go beyond the classroom for children in first grade and up who already know how to read and write.

- Children can experience other cultures and societies through the virtual trips they take using technology.

- Technology can also be a powerful tool for educators’ professional development.

Conclusion

An integrated curriculum is a written plan in which goals, objectives, and activities are laid out. It is recommended to have educational materials and evaluation strategies. To respond to young children’s needs, every curriculum should:

- ensure that it fosters a learning community in which both children and adults learn;

- highlight and stimulate learning and development in each child;

- establish clear, appropriate goals and expectations to encourage children’s holistic development;

- monitor the learning and development process using clear evaluation criteria;

- foster a relationship of mutual support between the school, family, and community.

An integrated curriculum is one in which the children’s interests and experiences serve as a basis for structuring rich experiences that establish connections between different subjects and areas of knowledge. An integrated curriculum is flexible and takes into consideration the cultural background, developmental stage, and learning style of the children. The integrated curriculum sees to the needs of children with handicaps and special needs in an inclusive environment. This requires a well-trained, sensitive teacher who is prepared to love and respect all children equally. Below, you can listen to a teacher planning an integrated curriculum.

Curriculum In Action

The Environment Adapted to the Curriculum

As an educator, you are the architect who designs an appropriate environment for children. It is up to you to provide an environment that is multicultural, with non-sexist experiences that help build the self-esteem of each child while also integrating them and their families into the classroom. This means that it should be non-discriminatory and that respect, acceptance, and appreciation of diversity should be the order of the day (Bredekamp, 1984).

Planned curriculum, based on learning as an interactive process. Educators develop an environment so that children learn through exploration and interaction with adults, other children, and the materials provided.

The classroom is the ideal environment to promote peace, tranquility, and the worth of each child. Classrooms are a physical space in which you and your students spend most of the day. For this reason I encourage you to create an attractive space with colors that are relaxing and stimulating and in which interpersonal relations are fundamental. In order to achieve this, you only have to visualize the environment as a very special place where everyone wants to be. You will have achieved this when you and your students feel that the physical space is important to you.

They will be independent in their environment if they are left to interact and resolve issues on their own or with other children (Vygotsky, 1988); this is the focus of a program that is based on developmentally appropriate practices. When they reach this stage of development, children can perform tasks by themselves, but they will also need the help of another person who can bring out the processes of analysis, reason, and action.

You will be asking yourself: but how can teachers master this? I will present some recommendations that you can follow:

- Plan educational experiences taking into account the interests, needs, and abilities of the children.

- Promote play as an educational strategy.

- Plan activities and use different materials that the children can relate to.

- Use a variety of strategies.

- Establish a daily routine.

- Be flexible and organized while following the daily routine.

- Make the schedule in blocks of time to allow for different activities.

- Make smooth transitions from one activity to another.

- Evaluate the program on a daily basis.

If you follow these recommendations, you will initiate a teaching-learning process in which the children engage in practicing their skills and building their knowledge (Bredekmap, 1986). The opportunities to ask, converse, make comments, and foster critical thinking are fundamental elements in a preschool environment.

- What do you remember about…?

- What do you think will happen?

- How do you know that?

- How do you know if they are different or the same?

- How can we resolve this issue?

- What alternatives do you propose?

- Why did you decide that?

- How would you feel if…?

- Why do you learn to use…?

- How can you show us what you learned?

(Kostelnik, Soderman & Whiren, 2004).

Write some more examples of these questions.

In your classroom, you will facilitate the development of curricular experiences, which will be organized in study modules that can be used over a specified amount of time (for example, two weeks, three weeks, or one month). Curricular development will also depend on the specific interests and needs of the students.

- What are the students’ interests?

- How can you find out?

- What elements do you take into consideration when designing your learning environment?

- What do you do to plan educational experiences?

- How can we organize study modules?

Integrated Curriculum: Successful Planning in a Preschool Environment

If you have decided to design a curriculum according to the parameters of the developmentally appropriate practices, it is important that you analyze what an integrated curriculum entails. In the first place, skills and theme-focused course content should be established and tied together. In studying thematic modules you will promote research skills, creativity, problem solving, language development, and humanism.

Planning an appropriate curriculum is based on observation and evaluation of the children’s specific needs, interests, abilities, and developmental stage (Bredekamp, 1986). The teacher has to take notes daily in order to adjust the modules depending on what the children really want and need to learn (see the Assessment module).

- What books are they reading?

- What are themes of these books?

- What are they showing interest in?

Take these interests and themes into consideration when developing the modules.

While planning, you should implement teaching strategies that help to achieve the goals established for the children participating in your learning program. These will be worked out according to children’s developmental areas: linguistic, cognitive, creative, physical, and emotional (intelligence). Below, I provide some practical ideas for strategies that you can use in your classroom.

STEPS FOR MODULE PLANNING

So that the modules are relevant, it is important to design them with your students. What are the steps to follow?

1. Explore the Topics

Exploring ideas can be done in collaboration with the children so that everyone will be familiar with the topics that will be studied in the educational environment. During this process, you can involve the parents, educators, and school staff.

- Tell me a bit about yourself.

- What do you like to do with your family?

- What are your hobbies?

- What is your favorite animal? Why?

- What do you like to learn with your classmates?

2. Choose the Topics

Once you have come up with some topics, choose those that are in line with the interests and needs demonstrated by the students, especially when considering the content of individual assignments.

3. Take an Inventory of Resources

Take into consideration the availability of human resources, materials, and equipment that you have at the school and in the classroom.

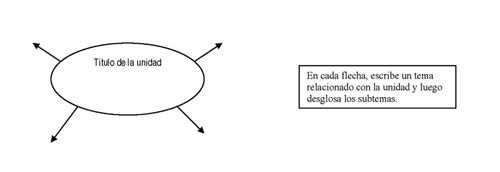

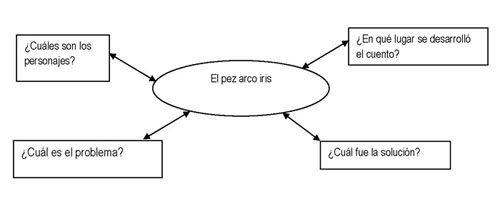

4. Prepare a Semantic Map of the Module

Elabora el mapa con los temas y conceptos a desarrollar. Un modelo esquemático para hacer el mapa puede ser:

5. Establish an Information System/Database

When creating a database, you should include objectives, abilities, outline of standards (for kindergarten), and some ideas for the implementation process (Kostelnik, Soderman & Whiren, 2004). This is what is referred to as module planning.

6. Outline a Daily Lesson Plan

There are various models of daily plans that correspond to the teacher’s needs and the requirements of the administration and supervisors. It is important to note that regardless of the plan’s structure, it is necessary to include the following:

- Objectives: specify what the children will do, learn, and how they will develop, as well as the way in which this will be accomplished.

- Skills: detailed expectations for each developmental area, important for academic achievement.

- Standards (for kindergarten): performance expectations that are achievable in comparison with the current performance level.

- Materials and equipment that will be used in class activities.

- Description of the activities according to the daily schedule.

- Evaluation strategy: detail the evaluation techniques and methods that will be used to evaluate children’s participation in activities, as well as the achievement of established objectives (see the Assessment module).

The planning process entails a reflection on the part of the educator, which involves “evaluating and validating the interest shown by the children, the effectiveness of the activities, and the results obtained. Let us reflect on the process that has been carried out, its complexity and simplicity, the strategies and materials used, and the ways in which we collect data.” (Cintrón, López, & Corujo, 1997, p. 187). From this starting point the next module or daily schedule can be planned.

- What other steps would you add? Why?

- Would you attempt to plan a module? Why?

Make a go at it!

Let’s Get to Work!

Let us plan taking into account what we have learned up to now. Remember:

- When planning, you should take into account the ages of the children that you are working with, as well as their experiences and needs.

- Each age group has certain characteristics. Therefore, your plan should reflect the appropriate level of difficulty for each group.

EXAMPLE OF A DAILY PLAN FOR INFANTS

DAILY PLAN FOR INFANTS

Module: Me

Topic: The Senses

Objectives

Infants will have the opportunity to:

- listen to stories and songs

- repeat words

- explore their environment and various textures

- imitate movements

- enjoy playing

- interact with the teacher/educator

Skills for Development Areas:

|

Development Areas

|

Level: Birth to One Year Old

|

|---|---|

| Linguistic | listening cooing making sounds using vocabulary words recognizing the teacher/educator’s voice |

| Physical | grabbing touching pulling themselves crawling walking |

| Emotional (Intelligence) | imitating hugging smiling playing crying interacting with the teacher/educator |

| Cognitive | pointing exploring observing examining |

| Creative | moving dancing creating |

Activities

|

Activities

|

Level: Birth to One Year

|

What other activities would you plan?

|

|---|---|---|

| Language | Story Time

The educator should choose an appropriate spot within the center to read a story to the infant. Read a story or book (that has texture) related to the topic. For example, the book This Is Not My Bunny (Watt, 2000). While reading, the educator can take the opportunity to encourage the child to touch the book and to talk about the rabbit that is in the story. The educator and infant can play a game that involves touching the textured surfaces in the book (the skin, clothes, hair, and other textures). |

|

| Sensory | Game: Find the Object

The educator prepares an area of the classroom by putting down a rug. Then place various objects with different textures and put the infants at one end of the rug so that they crawl over to the objects to hold and touch them. |

|